Your digging level

Description

Worldbeat is a pop-oriented fusion that blends contemporary Western production (pop, rock, dance, and electronic) with rhythms, instruments, scales, and vocal styles drawn from diverse musical traditions around the world.

It typically features layered percussion, polyrhythms, call-and-response vocals, and multilingual or code-switching lyrics, while maintaining accessible song forms and hook-driven choruses. Arrangements often juxtapose drum kits, bass guitar, and synths with instruments such as kora, mbira, oud, sitar, djembe, balafon, or charango. As a retail and radio category in the 1980s–1990s, worldbeat served both as a creative space for cross-cultural collaboration and a marketing umbrella, attracting praise for bridge-building and criticism for occasional exoticism or unequal credit-sharing.

History

The idea underlying worldbeat—melding Western pop/rock with non-Western musical traditions—took shape in the late 1970s and crystallized in the 1980s. Early signposts included Talking Heads’ African-influenced polyrhythms and the rise of multicultural festivals such as WOMAD (founded in 1982 by Peter Gabriel). The term “worldbeat” gained traction alongside the broader retail category “world music,” especially in the UK and US, to describe pop-facing hybrids rather than traditional or archival recordings.

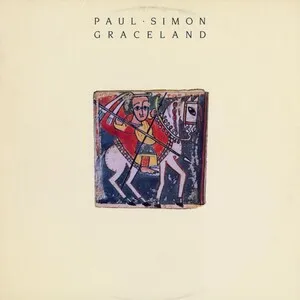

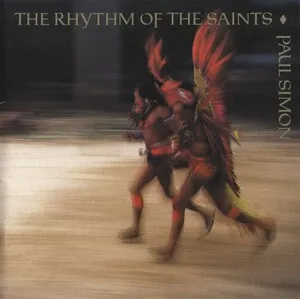

Mid-1980s releases popularized the sound worldwide. Paul Simon’s “Graceland” (1986) spotlighted South African township grooves and mbaqanga in a pop framework, while Peter Gabriel’s solo work and Real World Records (founded 1989) facilitated collaborations between Western producers and artists from Africa, Asia, and Latin America. Youssou N’Dour, Ofra Haza, and Sheila Chandra reached international audiences via radio and MTV, demonstrating worldbeat’s compatibility with mainstream formats.

The 1990s saw the rise of labels and curators (e.g., Luaka Bop, Putumayo) and projects such as Deep Forest and Afro Celt Sound System, which folded global vocal samples and traditional instruments into electronic and dance idioms. Manu Chao and Angélique Kidjo embodied a mobile, multilingual worldbeat ethos, blending ska, reggae, Latin, and Afropop elements with pop hooks. Cross-genre dialogues extended into trip hop, chillout, and indie electronic, further normalizing hybridized production.

Streaming platforms and global touring circuits accelerated exchange, making worldbeat less a discrete shelf category than a production approach informing global pop, indie, and electronic scenes. Artists increasingly co-create across continents, with improved visibility and credit for non-Western collaborators. Meanwhile, “global beats” playlists and festival programming continue to present worldbeat as an accessible entry point to cross-cultural music.

Worldbeat’s legacy is double-edged: it helped dismantle stylistic silos and amplified under-heard traditions, yet it has also prompted necessary critiques of power imbalances, sampling ethics, and the flattening of diverse traditions into a single market tag. Today, best practices emphasize equitable collaboration, proper attribution, and context-aware presentation—principles that have shaped modern world fusion, folktronica, and globally-inflected pop.