Your digging level

Description

Tibetan new age is a contemplative substyle of New Age that blends Tibetan Buddhist chant, ritual instruments (singing bowls, tingsha, dungchen long horns, gyaling oboes), and Himalayan modal idioms with spacious ambient production.

Tracks typically emphasize long drones, very slow tempos or free rhythm, pentatonic and modal writing, and mantra-based vocals delivered in earthy low-register chant or soft, breathy tones. Field recordings of monasteries, wind, and prayer wheels are often layered with synth pads and bowls to evoke a vast, alpine sense of place.

The result is music intended for meditation, yoga, and deep listening—less about harmonic progression than about sustained timbral bloom, resonance, and ritual atmosphere.

History

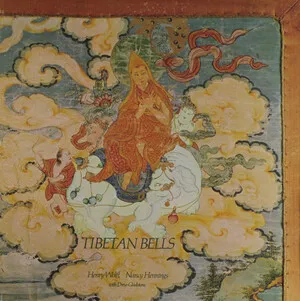

The style’s roots trace to the Western New Age and ambient movements that began embracing Himalayan sound-worlds. A landmark was Henry Wolff and Nancy Hennings’ Tibetan Bells (1972), one of the first studio albums to foreground Tibetan singing bowls as primary timbral material. These early explorations framed Tibetan ritual sonorities in a slow, spacious, and meditative context aligned with emerging New Age aesthetics.

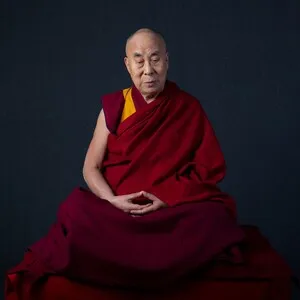

Through the 1980s, the broader New Age market grew, and labels and radio (e.g., Hearts of Space) helped normalize long-form, drone-based listening. In the 1990s, Tibetan new age gained definition as Tibetan diaspora artists and collaborators reached international audiences. Releases by Nawang Khechog, the Gyuto Monks Tantric Choir, and Lama Gyurme with Jean‑Philippe Rykiel brought authentic chant and instruments into contemporary ambient production. Labels such as New Earth Records, Celestial Harmonies, and Real World amplified the style’s visibility.

From the 2000s onward, the genre became a staple of meditation, yoga, and wellness playlists. Producers integrated higher-fidelity field recordings and sample libraries of bowls, horns, and monastery ambiences. Artists like Yungchen Lhamo, Klaus Wiese (posthumous reissues), and Jonathan Goldman (with Lama Tashi) further blended traditional chant with expansive, shimmering pads and deep drones.

Across decades, the core language—sustained resonance, ritual pacing, and mantra—remains steady. Modern productions employ longer reverbs, subtler dynamics, and wider stereo fields, but still prioritize the ceremonial intimacy and spaciousness that define the Tibetan soundscape.