Your digging level

Description

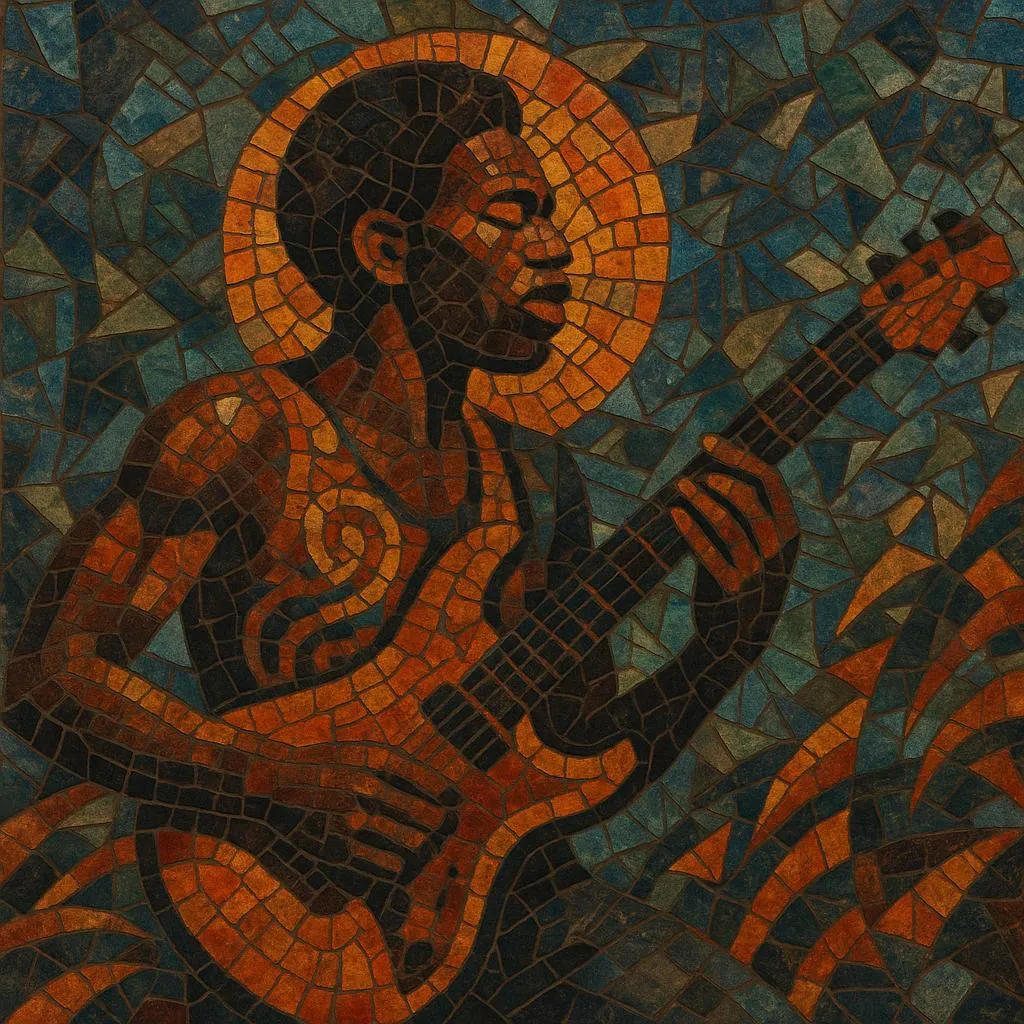

African rock is a broad umbrella for rock music created on the African continent, blending the instrumentation and song forms of Western rock with African rhythmic language, guitar approaches, and local languages.

From the late 1960s onward, bands across South, West, Central, and North Africa adapted garage, hard, and psychedelic rock to regional feels such as highlife, juju, mbaqanga, and soukous. The result spans fuzz‑driven “Zamrock” from Zambia and Zimbabwe, highlife‑rock from Ghana and Nigeria, South African alternative/indie scenes, and Sahel/Tuareg electric guitar styles that channel rock’s timbres through desert rhythms.

While the sound palette often features overdriven guitars, rock drum kits, and verse–chorus songwriting, the core identity comes from African polyrhythms, cyclical guitar ostinatos, call‑and‑response vocals, and modal or pentatonic melodies that localize rock idioms into unmistakably African grooves.

History

Rock and roll, British Invasion bands, and American blues reached African cities via radio, records, and touring groups in the 1960s. Urban dance bands already fluent in highlife, juju, mbaqanga, and soukous absorbed garage and beat‑group energy. In South Africa, groups such as Freedom’s Children and Hawk adapted psych and prog under the constraints of apartheid‑era circuits; in West Africa, Ghanaian and Nigerian club bands began amplifying highlife with rock backlines and electric guitar leads.

The early 1970s saw explosive cross‑pollination. In Ghana and Nigeria, highlife‑rock and teen psych bands (e.g., BLO, Ofege) pushed fuzz guitar, wah‑wah, and extended jams. In southern Africa, Zambia’s post‑independence scene birthed “Zamrock,” a raw fusion of hard rock, psych, funk, and local rhythms (e.g., WITCH, Amanaz, Ngozi Family). Zimbabwe’s Wells Fargo brought socially charged proto‑punk/psych. North and Sahelian players began electrifying desert traditions, foreshadowing later Tuareg guitar waves.

Economic downturns, censorship, and changing markets shrank some rock circuits, but scenes persisted. South African alternative and indie groups flourished in the late 1980s–1990s, while in the Sahel, exiled Tuareg guitar bands refined hypnotic, minor‑pentatonic grooves with rock timbres, laying groundwork for international breakthroughs.

Reissue labels and crate‑diggers revived interest in 1970s Afro‑rock and Zamrock, inspiring new bands on and off the continent. Tuareg/Sahel artists reached global stages with overdriven desert blues/rock. Meanwhile, contemporary African indie and heavy bands drew equally from local rhythms and global rock subgenres, reaffirming African rock as a living, diverse ecosystem rather than a single style.