Your digging level

Description

Mande music is the courtly and communal music of the Mande peoples (including Mandinka, Maninka/Malinke, and Bambara) whose heartland lies in present‑day Mali and extends across Guinea, Senegal, The Gambia, and Côte d’Ivoire. It centers on the hereditary jeli (griot) tradition of professional praise‑singers and instrumentalists who preserve genealogies, epics, and social histories.

Its core sound is built around cyclical ostinati (kumbengo) on instruments such as the 21‑string kora (harp‑lute), the balafon (gourd‑resonated xylophone), and the ngoni (lute), with improvisatory filigree (birimintingo) weaving above. Vocals alternate between composed refrains and free, declamatory passages (donkilo and sataro), often in call‑and‑response with a small chorus. Rhythms commonly breathe in 12/8 and 6/8 feels with subtle cross‑rhythms, while modal tunings (e.g., sauta, tomora) and timbral “buzz” aesthetics (from balafon resonators) shape a distinctive, shimmering texture.

Repertoires comprise named pieces tied to lineages and events (e.g., Sunjata epics, Duga, Kaira, Jarabi). In modern contexts, these materials underpin both acoustic ensembles and electrified bands, maintaining the social function of praise and mediation while speaking to contemporary audiences.

History

The Mande musical system crystallized alongside the rise of the Mali Empire and the Sunjata epic in the 1200s–1300s. Hereditary jeli (griot) lineages such as the Kouyaté, Diabaté, and Sissoko families became custodians of history, diplomacy, and ceremony, performing at courts and public events. Instruments like the balafon and ngoni anchored early ensembles; later the kora (in its present 21‑string form) became emblematic of jeliya (the art of the jeli).

Repertoires comprise praise‑songs and epics tied to patrons and lineages. Performances balance cyclical grooves (kumbengo) with virtuosic variations (birimintingo), and alternate between composed refrains (donkilo) and freer, rhetorical sections (sataro). Modal tunings (e.g., sauta, tomora ba/mesengo) and a 12/8 metric feel frame the sound, while the social function—mediating disputes, honoring patrons, and transmitting memory—remains central.

From the 1950s onward, field recordings and radio disseminated Mande music beyond its local contexts. After independence, state ensembles such as the Ensemble Instrumental National du Mali and Guinea’s orchestras (e.g., Bembeya Jazz National) adapted jeli repertoire for modern stages, blending it with horns and guitars. The Rail Band (Bamako) and Les Ambassadeurs modernized praise‑songs and helped launch artists like Salif Keita and Mory Kanté.

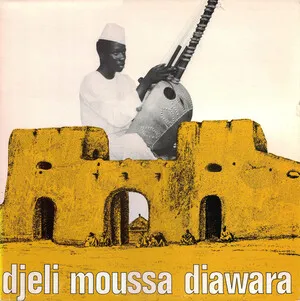

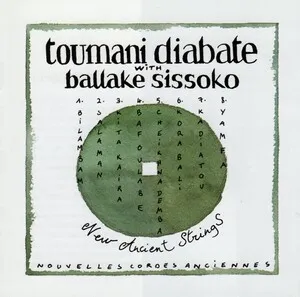

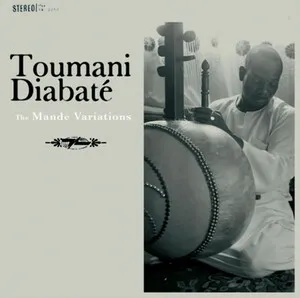

From the 1980s, kora and ngoni virtuosi—Toumani Diabaté, Ballaké Sissoko, Bassekou Kouyaté—brought jeliya to international audiences, collaborating with jazz, classical, and pop musicians. The repertoire’s adaptable cycles and modal tunings have continued to inspire worldbeat, Afro‑jazz, and desert‑blues scenes, while community ceremonies and family lineages sustain the tradition at home.