Your digging level

Description

Wassoulou is a contemporary popular music style from southern Mali and the wider Wasulu cultural area (spanning parts of Mali, Guinea, and Côte d’Ivoire). It blends village-based hunters’ music with modern, urban arrangements, centering the distinctive sonorities of the donso ngoni and its lighter cousin, the kamalen ngoni, alongside calabash percussion and handclaps.

The style is often led by powerful female vocalists singing in Bambara (Bamana) and related Mande languages, using call-and-response choruses, pentatonic melodies, and buoyant 6/8-to-4/4 cross-rhythms. Lyrics frequently address women’s perspectives—love, independence, social responsibility, marriage, and work—delivered with an earthy timbre and declamatory intensity that make Wassoulou both danceable and socially resonant.

History

Wassoulou draws from the musical practices of the Wasulu region in southern Mali, where hunters’ associations cultivated repertoires for the six-string donso ngoni (hunters’ harp), praise singing, and communal dancing. These traditions, rooted in Mande musical culture, used pentatonic scales, responsorial vocals, and trance-inducing rhythmic cycles.

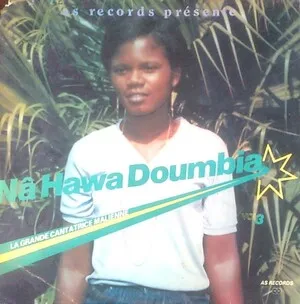

As rural-urban migration accelerated, Wasulu musicians adapted village repertories for city audiences in Bamako and beyond. Amplified kamalen ngoni (a lighter, “youth” version of the hunters’ harp), calabash, and hand percussion met electric bass and occasional keyboards. Early pioneers such as Coumba Sidibé, Sali Sidibé, and Nahawa Doumbia helped codify the style’s vocal approach, groove, and instrumentation.

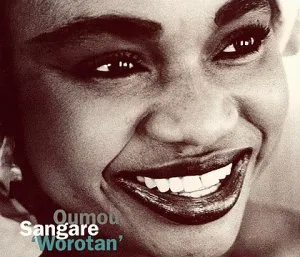

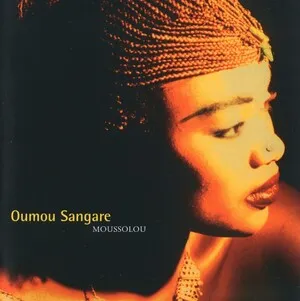

Oumou Sangaré’s emergence (notably with her 1989 album “Moussoulou”) propelled Wassoulou onto international stages, aligning with the global “world music” wave. The genre’s forthright, women-centered lyrics and entrancing grooves resonated with audiences, while tours and recordings refined a modern band format that still showcased ngoni timbres and call-and-response choruses.

Subsequent generations have blended Wassoulou with folk-pop, acoustic chanson, and subtle electronic textures, without losing its rhythmic lilt, pentatonic melodies, and social themes. Artists such as Fatoumata Diawara and Rokia Traoré have drawn on Wassoulou aesthetics in globally oriented productions, while Malian-based singers continue to anchor the tradition at home and in the diaspora.