Your digging level

Description

West African music is a broad regional tradition centered on cyclical grooves, polyrhythms, and call-and-response, carried by griot (jeli) storytellers and community ensembles. Its core sound is driven by interlocking percussion patterns—often in 12/8 or 4/4—anchored by bell timelines and hand drums, over which praise-singing, chant, and melodic ostinatos unfold.

Typical instruments include the kora (21‑string harp-lute), balafon (wooden xylophone), ngoni/xalam (lute), bolon (bass harp), talking drum, djembe and dunun, sabar, and shekere. Melodies tend to be modal and pentatonic, relying on repetition, variation, and improvisation. Islamic recitation and Sahelian court traditions contribute melismatic vocal styles and poetic structures, while coastal guitar idioms (palm‑wine, dance bands) shaped modern urban genres.

From Mande jeliya to Wolof sabar and Yoruba bata/talking-drum ensembles, West African music is both ceremonial and social—used for praise, weddings, initiations, communal work, and dance. Its rhythmic logic, timbral layering, and participatory performance practice profoundly shaped global popular music.

History

Oral-musical traditions predate written records, with drum, harp-lute, and xylophone lineages tied to ritual, agriculture, warfare, and praise. Call-and-response, timeline bells, and cross-rhythm (e.g., 3:2, 6:4) were already central, as was the role of hereditary musician-historians.

With the rise of the Mali Empire, Mande jeliya became a codified court art. Islamic scholarship and trade routes brought Sufi devotional aesthetics, poetic meters, and melismatic singing that blended with local forms, influencing Sahelian repertoires from Songhai to Hausa polities.

Port cities and missionary schools introduced guitars, brass, and harmony. Early 78‑rpm recordings captured griot ensembles and emerging coastal dance styles, laying groundwork for palm‑wine guitar idioms and urban band cultures.

Post‑colonial optimism fueled state bands and hotel circuits. Highlife (Ghana), jùjú (Nigeria), and dance‑band hybrids fused guitars and horns with traditional rhythms. Senegalese sabar innovations would soon crystallize as mbalax, while Malian/Guinean orchestras modernized griot repertoires.

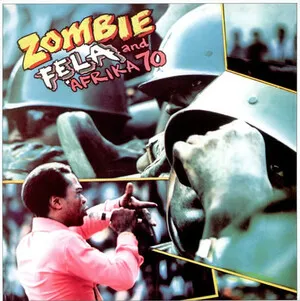

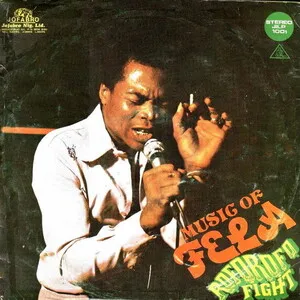

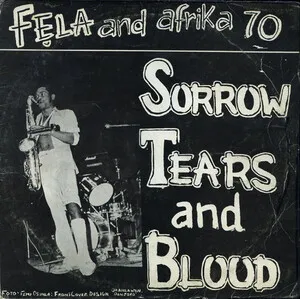

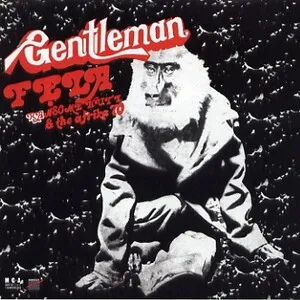

Fela Kuti’s Afrobeat fused Yoruba rhythm, highlife, and jazz into extended political grooves. In Mali and Guinea, kora/ngoni guitar stylings and Wassoulou vocal music gained international attention; desert blues from Tuareg communities (e.g., Tinariwen) reframed Sahelian modalities for global audiences.

Digital production, mobile studios, and pan‑African collaboration catalyzed Afrobeats (distinct from Afrobeat), hiplife, azonto, and hybrid pop/R&B. Traditional ensembles thrive alongside cosmopolitan scenes, with West African rhythmic DNA embedded in global pop, hip‑hop, and electronic music.