Your digging level

Description

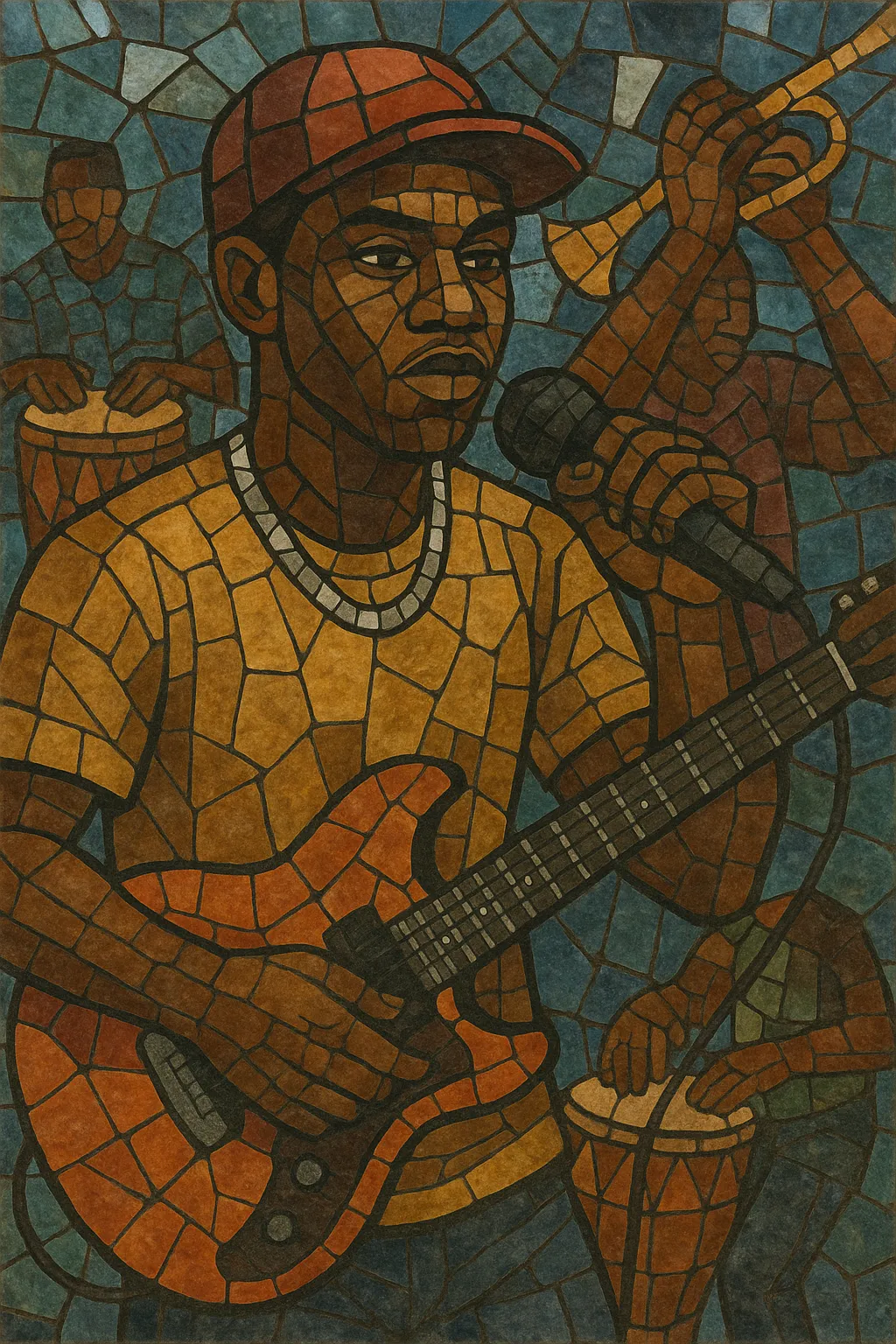

Hiplife is a Ghanaian fusion of classic highlife rhythms and melodies with hip hop’s rapped delivery, drum programming, and sampling aesthetics.

Built around mid‑tempo grooves, hiplife typically marries syncopated, guitar-led highlife riffs and horn stabs with hip hop drum patterns, dancehall energy, and catchy R&B‑style hooks. Artists rap predominantly in Ghanaian languages (Twi, Ga, Ewe) and Ghanaian Pidgin English, foregrounding local idioms, humor, social commentary, and storytelling.

The result is a vibrant, dance‑forward urban pop sound that remains unmistakably Ghanaian while being fully conversant with global rap and Caribbean diasporic styles.

History

Hiplife emerged in Ghana in the mid‑1990s as artists began blending the melodic and rhythmic DNA of highlife with the flow, sampling, and production of hip hop. Often credited as a principal pioneer, Reggie Rockstone popularized rapping in Twi over hip hop beats colored by highlife guitars and percussion. Early DJs, producers, and scene builders—such as Zapp Mallet, Jay Q, Panji Anoff (Pidgin Music), and later Hammer of The Last Two—shaped the genre’s sonic identity. Crews like Native Funk Lords (NFL) helped incubate the style in Accra’s clubs and on radio.

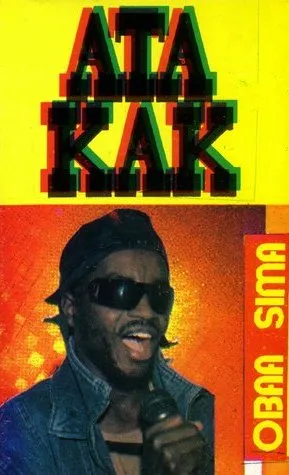

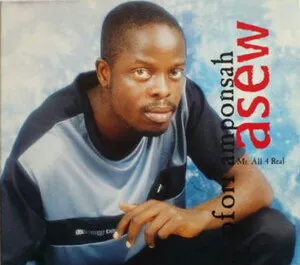

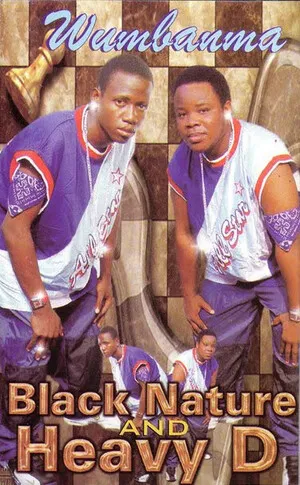

By the late 1990s and 2000s, hiplife had become Ghana’s dominant urban sound. Acts such as Obrafour, Lord Kenya, Buk Bak, VIP (later VVIP), Tic Tac (TiC), and Okyeame Kwame delivered hits that balanced party‑ready hooks with witty, proverbial lyricism. Production leaned on highlife chord cycles and palm‑wine‑style guitar licks fused with hip hop drums, reggae/dancehall accents, and choral call‑and‑response. National radio, mobile DJ culture, and awards circuits (e.g., the Ghana Music Awards) amplified the movement.

In the 2010s, hiplife both modernized and cross‑pollinated. Artists like Sarkodie, Edem, and Tinny updated flows and production with trap‑leaning drums, EDM‑polished synths, and Afrobeats’ pan‑African sheen, while still grounding choruses in highlife sensibility. The azonto wave—driven by dance culture and diaspora artists—crossed into global pop, with hiplife’s language use and rhythmic vocabulary embedded in the sound. The scene’s infrastructure and audience also paved the way for newer Ghanaian styles (e.g., Asakaa/hip hop drill) and a broader West African Afrobeats ecosystem.

A defining feature of hiplife is its embrace of Ghanaian languages and proverbial storytelling. Lyricists weave indigenous rhythms of speech, local humor, and social commentary into contemporary rap cadence, ensuring the music resonates deeply at home while remaining legible to global audiences through its groove and hooks.

How to make a track in this genre

Top albums