Your digging level

Description

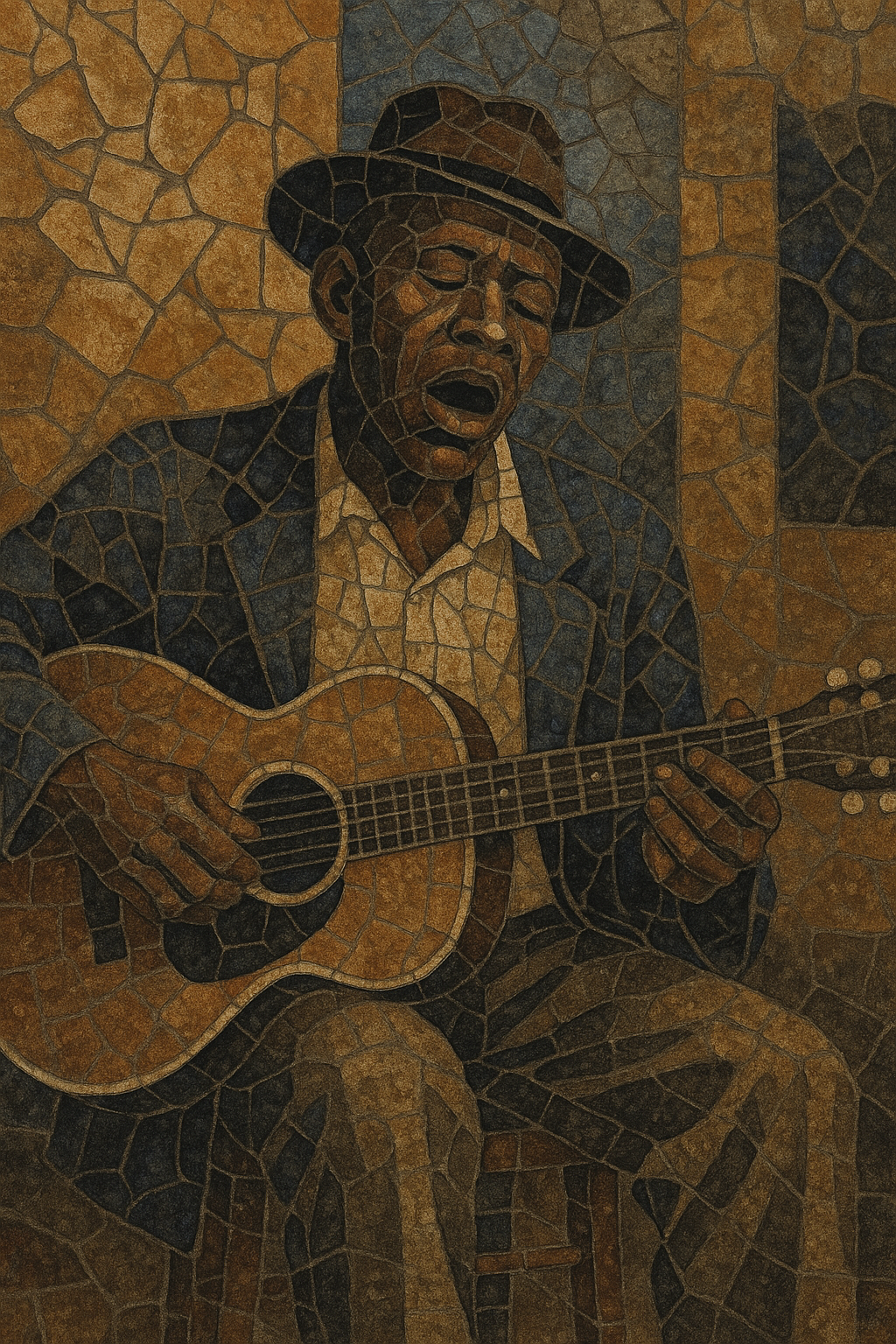

Pre-war blues refers to the acoustic, largely rural and early urban blues recorded and performed in the United States before World War II, roughly from the early 1920s through the late 1930s.

It encompasses several regional styles—most notably Delta (Mississippi), Piedmont (Southeast), Texas, Memphis, and St. Louis blues—as well as the "classic" female blues of the vaudeville and theater circuits, which featured powerful vocalists accompanied by small jazz ensembles. Hallmarks include expressive, melismatic singing, bent or "blue" notes, call-and-response between voice and instrument, slide guitar, ragtime-derived fingerpicking, and strophic verses often in an AAB lyrical pattern over 12-bar or related blues forms.

Lyrically, pre-war blues chronicles everyday life—work, migration, love, faith, injustice, and resilience—with a vivid mixture of poetry, metaphor, and lived detail. The sound world is intimate and direct, shaped by solo or small-ensemble performances captured to 78 rpm discs, and it provided the foundational vocabulary for later blues, R&B, rock and roll, and much of American popular music.

History

Blues emerges from African American musical practices in the U.S. South, drawing deeply on West African aesthetics filtered through slavery-era and post-Emancipation traditions. Field hollers, work songs, ring shouts, spirituals, and fiddle- and guitar-driven folk dance music supplied melodic contours, call-and-response organization, polyrhythmic feel, and the expressive use of bent or "blue" notes. By the 1910s, itinerant musicians were performing recognizable blues forms across Southern regions.

In 1920, Mamie Smith’s “Crazy Blues” catalyzed the race-records market, leading labels to record African American artists for Black audiences. Two parallel currents flourished: the "classic" blues singers (e.g., Bessie Smith, Ma Rainey) touring the vaudeville circuit with jazz-leaning accompaniment, and rural/country blues players (e.g., Blind Lemon Jefferson, Charley Patton) captured in field trips by A&R scouts. Regional idioms crystallized—Delta slide guitar and raw moans, Piedmont’s syncopated ragtime fingerpicking, and Texas’s more elastic phrasing.

Despite the Great Depression, the 1930s produced landmark sides by Robert Johnson, Skip James, Son House, and Mississippi John Hurt, alongside urbanizing strains in Memphis and St. Louis. Guitar-and-voice remained central, but piano, harmonica, and small combos were common, especially in classic blues. Collectors and folklorists (e.g., the Lomaxes) documented traditions, while 78 rpm technology standardized three-minute performances and shaped song forms, turnarounds, and instrumental breaks.

As migration moved musicians northward, amplified instruments and rhythm sections began redefining the idiom in Chicago and elsewhere. World War II rationing curtailed shellac production and effectively marks the end of the pre-war period. Nevertheless, pre-war recordings seeded post-war electric blues, jump blues, R&B, rock and roll, and a transatlantic folk/blues revival, ensuring the era’s stylistic DNA remained central to popular music.

How to make a track in this genre

Use voice with acoustic guitar as the primary setup; add slide (bottleneck) for Delta inflections or fingerstyle ragtime picking for Piedmont flavors. Harmonica and piano appear in many recordings; classic blues can feature small jazz combos (cornet/clarinet, piano, bass).

Base songs on 12-bar (I–IV–I–V–IV–I) or 8/16-bar blues variants. Employ dominant-seventh colors and the blues scale, leaning into flattened 3rd, 5th, and 7th degrees. Use a turnaround in bar 11–12 to cue new verses. Many lyrics follow an AAB scheme: the first line is stated, repeated with variation, then answered or resolved.

Favor a swung feel with elastic, speech-like phrasing; tempo can range from slow laments to mid/up-tempo dance numbers. In Piedmont styles, use alternating-bass thumb patterns with syncopated treble melodies; in Delta styles, let slide and vocal timbre carry the tension with spacious, rubato moments.

Write in concrete, lived language about love, labor, travel, injustice, faith, and survival. Employ metaphor, place names, trains/highways, and cyclical imagery. Deliver vocals with dynamic nuance—moans, falsetto cries, and growls—and engage in call-and-response with the guitar.

Explore open tunings (Open G, Open D) for slide; intonate expressive glissandi and microtonal inflections. Keep arrangements sparse to spotlight storytelling. Record or perform with intimate mic technique to preserve nuance, and leave space for short instrumental breaks or fills between vocal lines.