Your digging level

Description

American folk music is a broad family of traditional and vernacular musics that developed in the United States from the 19th century onward, drawing on British Isles balladry, African American spirituals and work songs, Native American traditions, and frontier songs.

It is typically acoustic, emphasizing voice and narrative over virtuoso display. Common instruments include acoustic guitar, banjo, fiddle, harmonica, mandolin, dulcimer, and upright bass. Forms are often strophic with repeated refrains, and melodies frequently use pentatonic or modal scales (Mixolydian, Dorian). Lyrical themes range from love, labor, faith, migration, and rural life to topical protest and social justice.

Regional styles—such as Appalachian ballads and string-band music, cowboy songs of the West, maritime shanties of New England, Cajun and Creole influences in Louisiana, and Midwestern and Southwestern dance tunes—sit under the umbrella of American folk, which later fed revivals and singer‑songwriter traditions.

History

American folk music coalesced during the 1800s as immigrant ballad traditions from England, Scotland, and Ireland met African American spirituals, field hollers, and work songs, along with Native American ceremonial and social musics. On the frontier and in rural communities, songs were transmitted orally, adapted to local life, and accompanied by portable instruments like fiddle, banjo, and later guitar.

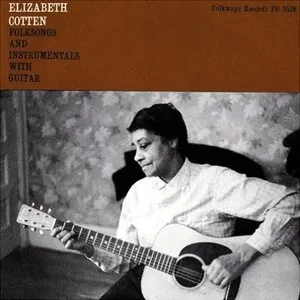

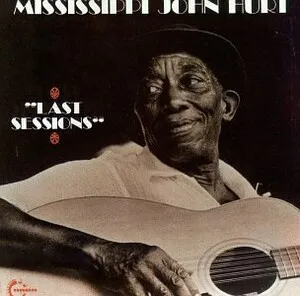

The late 19th and early 20th centuries saw folklorists (e.g., Francis James Child, Cecil Sharp, John and Alan Lomax) collect ballads, blues, and work songs across the U.S. The recording industry’s “race” and “hillbilly” series (1920s) captured country blues, string bands, and the Carter Family, making rural folk forms nationally audible. During the Great Depression, topical songs and Dust Bowl ballads (e.g., Woody Guthrie) framed folk as a voice of common people and social struggle.

After World War II, Pete Seeger, Lead Belly, and others popularized folk music in urban coffeehouses and political gatherings. The late‑1950s/early‑1960s folk revival brought collegiate audiences, hootenannies, and a surge of albums. Artists like Joan Baez, Odetta, and Bob Dylan connected traditional ballads to civil rights and antiwar movements, bridging folk traditions and contemporary protest.

Folk fed into electrified folk rock, country rock, and the singer‑songwriter movement. Meanwhile, regional traditions (Appalachian, Cajun/Creole, maritime, Southwestern) continued to evolve, bolstered by festivals and public media (e.g., Newport Folk Festival, PBS/NPR).

American folk persists as both preservation (old‑time, ballad singing) and innovation (indie folk, new weird America). Archival reissues, field recordings online, and community jams sustain the tradition, while contemporary artists blend folk idioms with pop, rock, and experimental production.

How to make a track in this genre

Use primarily acoustic instruments: voice, guitar (fingerpicking or strumming), banjo (frailing/clawhammer), fiddle, harmonica, mandolin, upright bass, and Appalachian dulcimer. Keep arrangements intimate; two to four parts often suffice. Prioritize vocal clarity and lyric storytelling.

Write singable melodies in major (Ionian) or modal scales (Mixolydian, Dorian); pentatonic contours are common. Harmonies are simple (I–IV–V; occasional ii or vi) with sparse extensions. Rhythms are steady and dance‑derived (reels in 2/4, waltzes in 3/4), or free when ballad‑like. Consider drones or open tunings (e.g., DADGAD, open G) for modal color.

Use strophic forms with refrains or call‑and‑response. Tell concrete, scene‑rich stories about work, travel, love, injustice, and community. Favor plain language, strong imagery, and memorable choruses. Topical songs should be specific yet universal enough to invite audience participation.

Sing with direct, unadorned tone; light ornamentation and close harmony (duos/trios) work well. Encourage audience choruses and communal feel. Record with minimal processing; room mics and live takes capture authenticity.