Your digging level

Description

The Greenwich Village scene refers to the acoustic folk- and blues-centered singer‑songwriter movement that coalesced in the coffeehouses, clubs, and streets of Greenwich Village in New York City during the late 1950s and especially the early to mid‑1960s.

Rather than a single strict musical genre, it was a fertile urban hub where traditional American folk, country blues, and topical songwriting converged. Artists favored intimate, lyric‑driven songs performed with acoustic guitar, unadorned vocals, and occasional harmonica, emphasizing storytelling, social commentary, and a direct connection with audiences.

The scene’s clubs—Gerde’s Folk City, the Gaslight Café, Café Wha?, and Café Au Go Go—nurtured emerging writers who transformed folk traditions into contemporary protest, confessional, and narrative songs, laying the groundwork for the modern singer‑songwriter and the rise of folk rock.

History

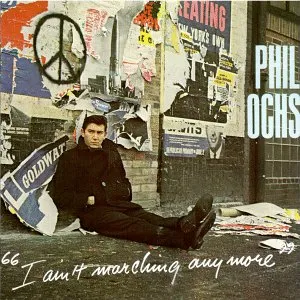

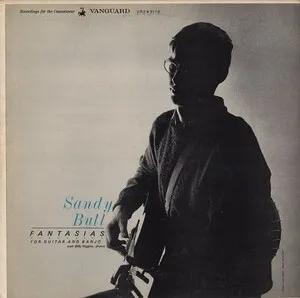

Greenwich Village, already a bohemian enclave and Beat gathering place, became a magnet for young musicians, poets, and activists. Washington Square Park hootenannies and open mics at venues like Gerde’s Folk City and the Gaslight Café brought together traditional ballad singers, country‑blues interpreters, and new songwriters. Independent labels (Folkways, Elektra, Vanguard) and magazines (Sing Out!, Broadside) amplified the movement’s grassroots ethos.

A wave of artists emerged with original, topical, and narrative material that resonated with the civil rights movement and, soon, anti‑war sentiment. The repertoire mixed reimagined folk standards with sharp, contemporary lyrics. Peter, Paul and Mary brought polished harmony singing to mass audiences, while Bob Dylan’s early albums and songs (e.g., Blowin’ in the Wind) made the Village’s songwriting voice internationally influential.

As the scene matured, some artists—most famously Dylan in 1965—embraced amplification and rock rhythms, catalyzing folk rock. While many Village performers remained acoustic, the shift expanded the music’s reach and introduced more complex studio production and band arrangements, linking Village songwriting to broader pop and rock currents.

The scene seeded the modern singer‑songwriter tradition and influenced successive folk revivals, indie folk, psych folk, and anti‑folk movements. Its club culture and street‑level song exchange created a durable model for urban songwriting communities, where narrative craft, plainspoken vocal delivery, and social engagement remain central values.