Your digging level

Description

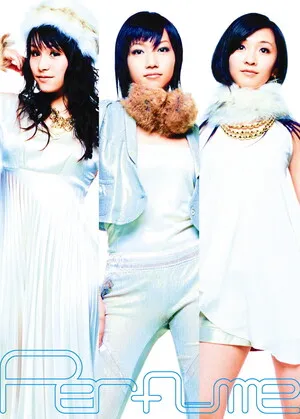

Japanese idol is a pop-centered entertainment phenomenon built around singers and groups whose appeal blends catchy, polished songs with a carefully crafted public image, approachable personalities, and tightly synchronized choreography.

Musically it spans bright, hook-forward dance-pop and electropop to tender ballads, often arranged in the familiar J-pop structure of A-melody, B-melody, and a soaring, repeatable chorus (sabi). Production favors clean vocals, layered harmonies, glittering synths, and chantable hooks designed for audience call-and-response.

Beyond sound, the genre is defined by its ecosystem: fan events (handshakes, photo ops), wotagei (coordinated cheers), member rotations, and an emphasis on growth arcs and parasocial closeness. Female and male idol scenes developed in parallel, feeding broader J-pop and otaku culture while continually reinventing themselves through large-scale collectives and alternative/underground offshoots.

History

Japanese idol culture emerged in the early 1970s from the kayōkyoku mainstream, borrowing the Western teen-idol model and bubblegum pop directness. Early icons like Momoe Yamaguchi, Candies, and Pink Lady set the template: photogenic singers, media ubiquity, and concise, hooky songs with choreography.

The 1980s saw an explosion of star-making through TV variety shows, talent contests, and magazines. Seiko Matsuda and Akina Nakamori became era-defining solo idols. Onyanko Club pioneered the large-member, school-uniform aesthetic and fan-participation model that later groups would refine, while the music blended kayōkyoku melodicism with increasingly modern pop and dance touches.

Shifts in the market and the rise of singer-songwriters briefly cooled the classic idol boom, but male idols (driven by Johnny’s agencies) dominated TV and charts. Production values modernized toward glossy J-pop, while female idol presence incubated in smaller agencies and audition ecosystems.

AKB48 (2005–) revolutionized the format: permanent theater shows, large rotating rosters, fan voting (senbatsu elections), and frequent singles engineered for participation. Hello! Project’s Morning Musume sustained a parallel lineage with generational member additions. The sound leaned into dance-pop and electropop, keeping ballads for sentimental arcs.

The scene fragmented and innovated. Sakamichi Series (Nogizaka46, Keyakizaka/櫻坂46) refined a more elegant or conceptual image. Alternative/underground idols mixed punk, metal, and avant-pop (e.g., kawaii metal and anti-idol movements), attracting global attention. Tie-ins with anime, games, and otaku events deepened, while wotagei culture standardized choreographed cheering.

Idol acts increasingly tour abroad, stream globally, and collaborate with producers across pop, EDM, and rock. The format’s training systems, multimedia storytelling, and fan-driven economics continue to shape broader J-pop and influencer-era music marketing, even as indie and alt-idol scenes push sonic and thematic boundaries.