Yoruba music refers to the traditional and popular musical practices of the Yoruba people of southwestern Nigeria and neighboring regions. It is built on polyrhythmic drum ensembles, call‑and‑response vocals, and praise poetry (oríkì) that celebrates deities, lineages, and notable individuals.

Core instruments include the dùndún (talking drum) family, bàtá drums used in Òrìṣà ceremonies, sẹ̀kẹ̀rẹ̀ (gourd rattle), agogô (iron bell), sakara (frame drum), omele (support drums), and agídìgbò (a box lamellophone/bass thumb piano). Melodies closely follow the tonal contours of the Yoruba language, while lead drummers “speak” phrases on pressure drums.

Across the 20th century, Yoruba music provided the foundation for modern styles such as jùjú, apala, sakara, waka, and fuji, and strongly informed pan‑African and global genres like afrobeat and afrobeats.

Yoruba musical practice predates colonial contact and is deeply tied to religion, social organization, and praise poetry. In palace, shrine, and marketplace contexts, drum ensembles organized around bell timelines and interlocking parts supported dance, ritual, and oríkì recitation. The dùndún (talking drum) and bàtá families became emblematic, with lead drummers reproducing speech tones and dialoguing with singers and dancers.

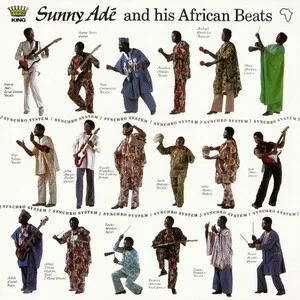

Urban growth in Lagos, Ibadan, and other towns fostered hybrid ensembles. Sakara (frame‑drum led) and apala (rattle- and drum‑led) developed among Muslim Yoruba, blending Qur’anic vocal stylings with indigenous rhythms. Guitar‑based bands, influenced by palm‑wine and highlife currents, catalyzed jùjú, which retained Yoruba percussion (shekere, agogô) and call‑and‑response while adding guitars and later pedal steel.

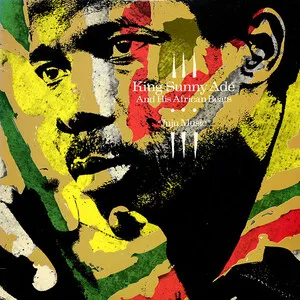

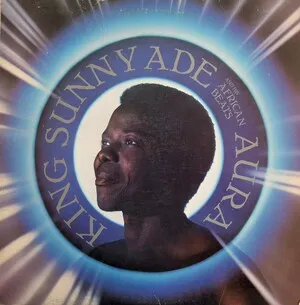

From the 1940s to 1970s, artists codified Yoruba popular genres: I.K. Dairo, Tunde King, and later King Sunny Adé and Ebenezer Obey globalized jùjú’s supple groove. Waka emerged with powerful women vocal leaders (e.g., Salawa Abeni), while Yoruba folk opera and travelling theatre troupes integrated music, dance, and drama.

In the 1970s–90s, fuji evolved from Islamic were (Ramadan dawn songs), led by Sikiru Ayinde Barrister and Kollington Ayinla, combining dense percussion sections, melismatic vocals, and audience‑interactive praise. Meanwhile, Yoruba rhythmic and poetic aesthetics infused afrobeat and, later, contemporary afrobeats—both of which carry Yoruba drum feels, language, and performative energy into global pop.

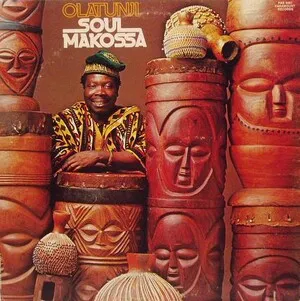

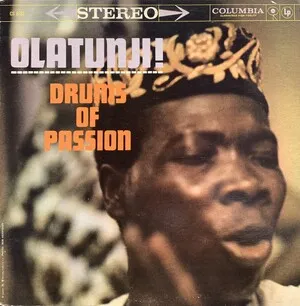

Diasporic links (e.g., batá traditions in the Americas) and international collaborations (master drummers and bandleaders) helped spread Yoruba techniques. Today, ceremonial drumming continues in sacred contexts, while modern bands, hip‑life/highlife fusions, and Nigerian pop maintain core Yoruba features of polyrhythm, tonal text setting, and call‑and‑response.