Your digging level

Description

Italian folk music encompasses a mosaic of regional traditions that developed across the Italian peninsula and islands, each with distinct languages/dialects, instruments, dance rhythms, and vocal practices. While the roots reach far back, the repertoire and identity we recognize today were largely documented and consolidated from the 19th century onward.

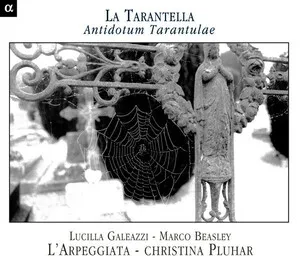

Characteristic elements include lively dance forms such as tarantella, pizzica, saltarello, and tammurriata; robust polyphonic traditions like Sardinia’s canto a tenore and Liguria’s trallalero; narrative stornelli and ballads; and ritual songs tied to the seasons, work, and devotion. Typical instruments are frame drums (tamburello/tammorra), diatonic accordion (organetto), Italian bagpipes (zampogna) with shawm (ciaramella), launeddas (Sardinia), chitarra battente, mandolin, and fiddle. Modal melodies, drones, and call-and-response vocals are common throughout.

Beyond entertainment, the music historically served social and spiritual functions—from communal dance to religious processions and even the famous (and debated) "tarantism" healing rituals in the South. In modern times it thrives in both local festivities and the global world-music circuit.

History

Italian folk music emerges from centuries of local practice shaped by geography, language, religion, and community life. From Alpine valleys to Mediterranean coasts, distinct micro-traditions evolved: tarantella and pizzica in the South; saltarello in the Center; work songs and stornelli across rural areas; Sardinian polyphony (canto a tenore) and Ligurian trallalero; and devotional repertoires tied to Catholic feasts and processions. Instruments such as zampogna–ciaramella pairs, launeddas, chitarra battente, and frame drums accompanied singing and dance.

During the 1800s, growing interest in folklore led collectors, scholars, and local musicians to notate and record songs. Urbanization and mass migration (both internal and overseas) altered performance contexts, but also spread melodies beyond their original communities. The early recording industry captured dialect songs and area-specific styles, while civic bands and mandolin orchestras bridged popular and folk worlds.

After WWII, folklorists and ethnomusicologists (notably Diego Carpitella and collaborators, alongside international figures like Alan Lomax during his 1954 Italian recordings) systematically documented regional repertoires. The 1960s–70s folk revival fostered ensembles that reinterpreted traditional music on stage and record, balancing respect for local style with new arrangements and political/poetic currents.

From the 1990s, events like La Notte della Taranta spotlighted Salento’s pizzica and helped renew national and international interest. Sardinian tenores toured globally; Ligurian trallalero choirs and Southern tammurriata groups revitalized processional and dance contexts. Today, Italian folk thrives in festivals, conservatories, and cross-genre projects (folk-rock, world fusion), while communities maintain oral transmission in seasonal rites and village celebrations.