Your digging level

Description

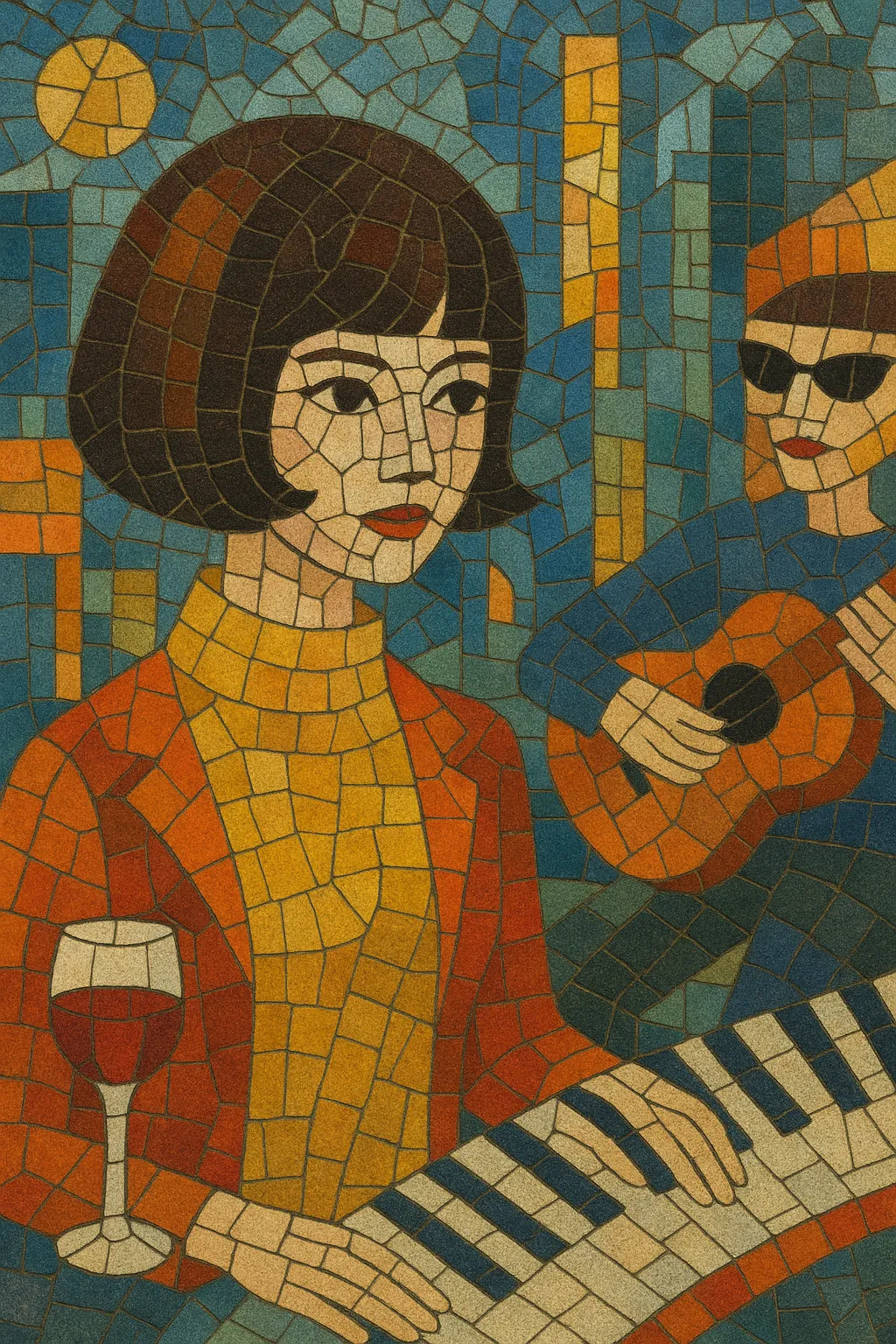

Shibuya-kei is a Japanese pop micro‑genre that emerged from Tokyo’s Shibuya district in the early–mid 1990s. It blends 1960s French yé‑yé, bossa nova, lounge/easy listening, baroque pop, jazz, sunshine pop, and slick city‑pop with contemporary sampling and electronic production.

The style is cosmopolitan and retro‑futurist: it celebrates crate‑digging, witty pastiche, and graphic design/fashion as much as music. Songs often feature breezy melodies, airy or whispery vocals in Japanese, English, or French, and richly orchestrated arrangements that feel both nostalgic and playful.

History

Shibuya-kei took shape around Shibuya’s record stores (notably Tower Records and HMV) and indie labels where musicians and fans obsessed over imported vinyl. Artists such as Flipper’s Guitar began hybridizing British indie and 1960s European pop with Japanese sensibilities, setting the stage for a localized, crate‑digging pop movement.

Labels like Readymade (Yasuharu Konishi of Pizzicato Five), Trattoria (Keigo Oyamada/Cornelius), and Crue‑L Records provided a home for producers who sampled exotica, bossa nova, lounge, and jazz, then framed them with modern beats and sleek graphic identities. Pizzicato Five’s chic pop and Cornelius’s kaleidoscopic sample collages helped codify the sound’s retro‑futurist wit and international flair.

Shibuya-kei filtered abroad via boutique labels and magazines, then achieved wider reach when Cornelius’s “Fantasma” (1997) and Pizzicato Five compilations appeared on Western imprints. Towa Tei, Kahimi Karie, Fantastic Plastic Machine, and Buffalo Daughter further connected Shibuya-kei to global downtempo, acid jazz, and club cultures.

As Japanese mainstream tastes shifted toward R&B/hip hop and dance‑pop, many Shibuya-kei figures broadened into experimental pop or sleeker electropop. The movement’s DNA—crate‑digging chic, internationalist references, and design‑minded presentation—lives on in picopop, parts of alternative idol production, and contemporary Japanese indie/electropop, as well as in internet micro‑genres that riff on retro media and easy‑listening atmospheres.

How to make a track in this genre

Aim for a retro‑futurist collage: treat 1960s pop, French yé‑yé, bossa nova, lounge, and jazz as a color palette, then reframe them with modern pop/electronic production. Keep things light, stylish, and slightly ironic.

Use jazzy, colorful chords (major 7ths, 9ths, ii–V–I turns), circle‑of‑fifths motion, and modulations that evoke film music and 60s easy listening. Melodies should be catchy yet airy—often sung in soft registers, sometimes in English or French for cosmopolitan flavor.

Blend bossa nova/samba patterns, swinging 60s go‑go beats, and mid‑tempo 4/4 pop. Sprinkling breakbeat or light house/downtempo drums is common; keep grooves crisp but not heavy.

Combine sampled vinyl snippets (exotica flutes, vibraphone, strings, harpsichord, vintage horns) with drum machines and clean bass. Layer hand claps, shakers, and percussion for sparkle. Use tasteful reverb and tape/analog coloration to evoke retro warmth without lo‑fi murk.

Structure songs like classic pop: short intros, verse/chorus hooks, concise bridges. Employ sample‑based motifs and call‑and‑response between vocals and riffs. Interludes can feature found sounds, radio idents, or faux‑advert jingles to underline the ‘boutique’ aesthetic.

Keep lyrics playful, urbane, and image‑rich—references to cafés, fashion, and travel fit well. Visual identity (typography, photography, sleeve design) is integral; think magazine‑ready minimalism.

Clear samples where appropriate, or recreate the mood with original parts. Study 1960s French/Italian library music, bossa records, and city‑pop to internalize phrasing and arranging conventions.

Top albums