Your digging level

Description

Foxtrot is a lightly syncopated ballroom dance style in 4/4 time, designed for smooth, traveling steps across the dance floor.

Musically, it is closely associated with early jazz and the dance-band tradition, often featuring clear, steady quarter-note pulse, elegant phrasing, and arrangements that balance melodic clarity with subtle swing.

Although it originated earlier, it became especially popular during the big-band era and remained a core standard of ballroom repertoire, with both “slow foxtrot” and faster variants circulating in social dance and stage performance.

History

Foxtrot emerged in the United States during the 1910s as a modern social dance form set to popular and jazz-influenced dance music.

Its defining musical identity formed around a steady 4/4 groove with light syncopation that supported long, gliding steps.

In the 1920s, foxtrot became a mainstream ballroom staple alongside the growth of professional dance orchestras and early jazz bands.

During the 1930s, big bands and hotel ballrooms helped cement foxtrot’s association with early big-band jazz arranging: sectional call-and-response, clear melodic statements, and dance-friendly structure.

As swing dancing and later rock-and-roll shifted popular dance culture, foxtrot remained central in ballroom pedagogy and competition.

It continues today as a foundational ballroom genre, often performed with refined orchestration or modern “standard” ballroom interpretations that keep the same 4/4 walking pulse and elegant phrasing.

How to make a track in this genre

Write in 4/4 with a clear, steady pulse that a dancer can “walk” to.

Use light syncopation (anticipations, off-beat accents, or swung eighth-note figures) without obscuring the downbeat.

Aim for a moderate tempo for classic foxtrot; slower, smoother tempos suit “slow foxtrot” interpretations.

Build the groove around a consistent quarter-note drive (bass and rhythm section), keeping the feel smooth and buoyant.

If using a jazz approach, keep swing tasteful rather than aggressively syncopated, so the dance remains gliding rather than bouncy.

Use functional harmony common to American popular song and early jazz: II–V–I motion, secondary dominants, turnarounds, and occasional chromatic passing chords.

Keep harmonic rhythm clear (often one to two chords per bar) so phrasing remains dance-friendly.

Write memorable, singable melodic lines with balanced phrases (often 4-bar and 8-bar units).

Common song forms include AABA (32-bar) and verse–chorus designs, with clear cadences that dancers can feel.

A classic approach uses dance-band or early big-band forces: brass section, reeds/saxes, and rhythm section (piano, guitar/banjo, upright bass, drums).

Arrange with clean sectional textures: melody stated by reeds, answered by brass, supported by steady rhythm.

Include short instrumental interludes or shout-like passages, but keep the overall structure predictable and floor-friendly.

If writing a vocal foxtrot, lyrics typically match the dance’s social elegance: romance, nightlife, sophistication, and nostalgic sentiment.

Prioritize clear diction and a melody that sits comfortably over the steady 4/4 pulse.

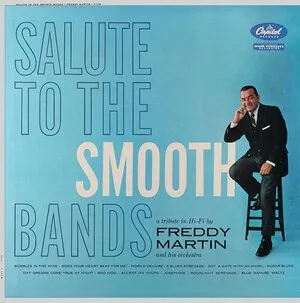

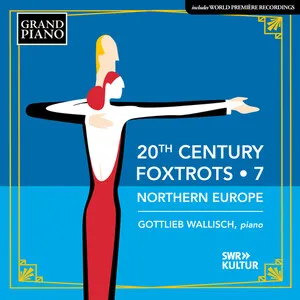

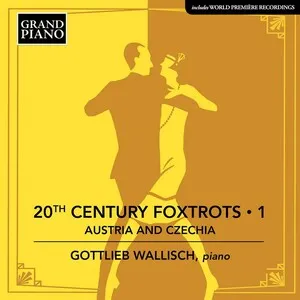

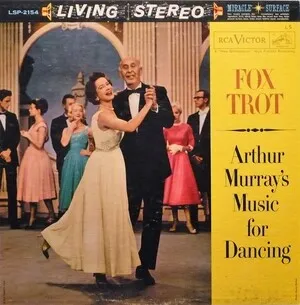

Top albums

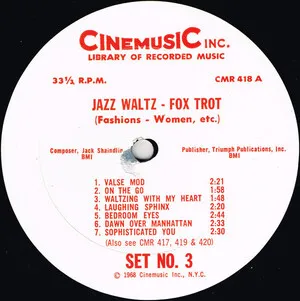

%20%2F%20Fox%20Trot%20(Fashions%20-%20Distaff%20Side%2C%20Etc_)%2C%20Cover%20art.webp)