Finnish folk music encompasses two intertwined traditions: the ancient Kalevala‑meter runo singing and kantele music, and the later pelimanni (dance‑fiddler) repertoire shaped by pan‑Nordic and Central European dance forms. The older layer features trochaic tetrameter verses with alliteration and parallelism, often sung solo or antiphonally and accompanied by small kanteles or performed unaccompanied. The newer layer centers on village dance bands with fiddles, accordion, harmonium, and bass playing polskas, polkas, schottisches (jenkka), mazurkas, waltzes and minuets.

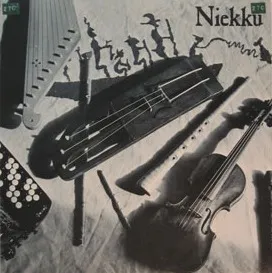

Typical timbres range from the bell‑like shimmer of the kantele and the droning, nasal tone of the jouhikko (bowed lyre) to the bright, driving sound of twin‑fiddle and accordion leads. Modal colors (Dorian, Aeolian, Mixolydian), drone tones, heterophony, and subtle asymmetric lilt in triple‑time dances are common. Themes span myth and magic (as preserved in the Kalevala), nature imagery, work and wedding songs, and witty, strophic “rekilaulu” ballads borrowed and localized from broader European song currents.

Finnish folk music rests on an ancient stratum of Finnic runo singing and kantele practice. The runo tradition, characterized by trochaic tetrameter, formulaic poetry, and call‑and‑response performance, was sustained in Karelia and eastern Finland well into the 19th and early 20th centuries. Instrumental counterparts included small kanteles and the jouhikko (bowed lyre), whose droning strings and modal melodies suited the incantatory poetry.

The 1800s saw intensive song collection and the compilation of the national epic Kalevala, which elevated runo singing as a symbol of Finnish identity. At the same time, Western and Nordic dance fashions—polska, polka, schottische (jenkka), mazurka, waltz, and minuet—spread through villages. Local pelimanni (dance‑fiddlers) adapted these styles, creating a distinctly Finnish dance tradition for fiddle, later joined by accordion, harmonium, and bass.

By the early 20th century, regional pelimanni idioms (notably around Kaustinen) were flourishing. Field collectors documented both runo songs and dance tunes as modernization threatened oral transmission. From the 1960s onward, revival movements professionalized ensembles (e.g., Tallari), festivals (Kaustinen Folk Music Festival) energized the scene, and musicians reintroduced older instruments such as the jouhikko and small kanteles. Finnish‑Swedish communities also preserved parallel pelimanni repertoires.

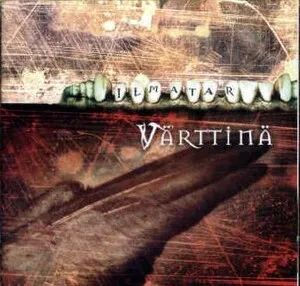

Since the late 20th century, Finnish folk has expanded outward: neo‑folk vocal groups (e.g., Värttinä) reimagined runo aesthetics; virtuosic accordionists and fiddlers modernized pelimanni arranging; and experimental artists fused folk timbres with rock, jazz, and electronic textures. Today, Finnish folk music is simultaneously archival, community‑based dance music, and a platform for innovative, globally visible artistry.