Christian liturgical music is the body of sacred musical practices created to accompany the public worship (liturgy) of Christian churches.

It encompasses a wide spectrum of traditions and forms, from ancient monophonic chant (e.g., Gregorian, Byzantine, Syriac) through Renaissance a cappella polyphony and Baroque sacred concerted styles, to modern liturgical hymnody and contemporary sacred works. Its musical language is shaped by scripture and authorized liturgical texts, aims to support prayer and ritual action, and privileges clarity of the Word, reverence, and congregational participation.

While instrumentation and style vary across denominations and eras, core features include text-driven melodies, modal or diatonic harmony, responsorial and antiphonal textures, and formal structures aligned to the Mass/Divine Liturgy and the Daily Office (e.g., psalms, hymns, canticles).

Early Christian worship emerged within the Roman Empire, drawing directly on Jewish synagogue and Temple chant, psalmody, and cantillation. After the Edict of Milan (313 CE), Christianity’s public status enabled more formalized rites and wider musical codification.

Regional chant families (e.g., Old Roman, Ambrosian, Mozarabic, Gallican, Byzantine) developed to serve local rites. In the Latin West, the Carolingian synthesis produced the standardized Gregorian chant—monophonic, modal, and free-rhythmic—becoming the bedrock of Western liturgical music. Eastern traditions (Byzantine, Syriac, Coptic, Armenian) codified their own modal systems and hymnographic repertoires.

Organum and early polyphony grew from chant. By the Renaissance, composers such as Josquin, Palestrina, Victoria, Tallis, and Byrd refined imitative a cappella textures for the Mass and Office. Liturgical humanism emphasized textual intelligibility and balanced counterpoint.

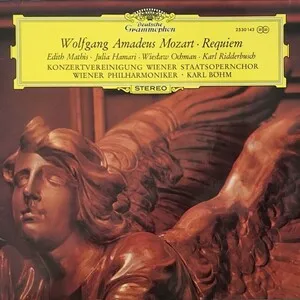

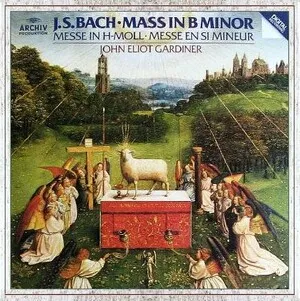

The Reformation diversified liturgical practice: Lutheran chorales, metrical psalms in Reformed contexts, and the continued Roman Catholic tradition shaped distinct idioms. The Baroque era introduced concerted sacred styles, cantatas, passions, and oratorios; organs and instrumental ensembles took larger roles while still serving liturgical frameworks.

Romantic, national, and revivalist movements renewed interest in chant and Orthodox polyphony; shape-note and gospel currents energized congregational song. The 20th century saw vernacular reforms, renewed chant scholarship, and minimalist sacred idioms (e.g., Pärt, Tavener). Today, Christian liturgical music spans ancient chant to contemporary hymnody, adapting to language, culture, and pastoral needs while centering worship.

Aim for reverence, clarity of sacred text, and support of ritual action. Let the music serve the liturgy: the Word and the assembly’s prayer come first.