A motet is a polyphonic vocal composition, usually on a sacred Latin text, that emerged in the High Middle Ages and became a central genre of European art music during the Renaissance. Early motets layered different texts and rhythms above a chant-derived tenor, while later Renaissance motets favored smooth, imitative counterpoint shared among voice parts.

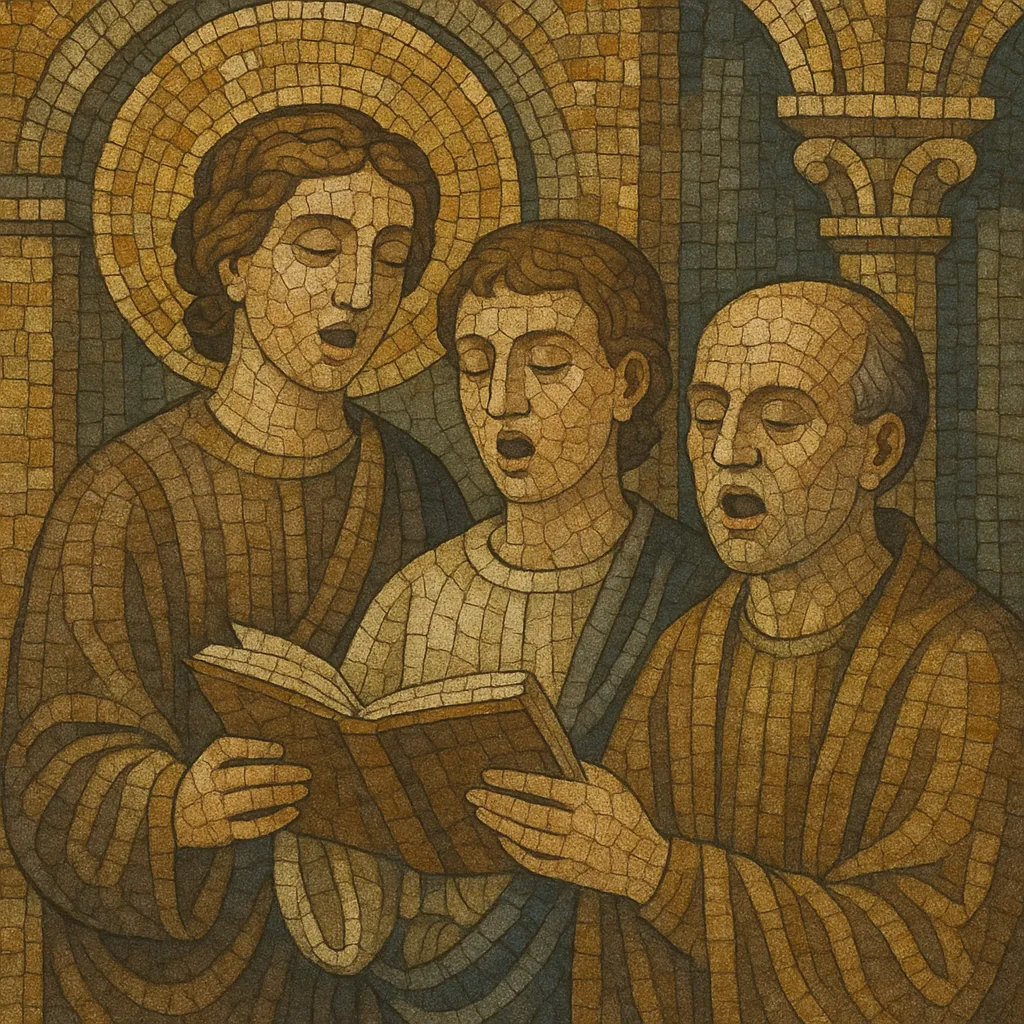

Across its long history the motet served both liturgical and devotional functions, typically performed a cappella by small choirs. Stylistically it ranges from the rhythmically intricate, isorhythmic constructions of the 13th–14th centuries to the balanced, text-sensitive writing of the 16th century, and onward to concerted and chorale-based treatments in the Baroque and beyond.

The motet originated in 13th‑century Paris, evolving from the practice of adding new texts (motetus) to upper voices of clausulae derived from Notre Dame organum. A chant fragment (cantus firmus) in long notes anchored the tenor while one or more upper parts sang newly composed lines—often with contrasting texts and meters. This period (Ars antiqua) produced early Latin and vernacular motets that were rhythmically stratified and often syllabic in declamation.

In the 14th century, composers such as Philippe de Vitry and Guillaume de Machaut refined the genre with isorhythm—repeating rhythmic patterns (talea) paired with repeating melodic segments (color) in the tenor. These works could be ceremonial or political as well as sacred, featuring complex syncopations and multiple texts, and they represent the height of medieval rhythmic innovation.

By the early Renaissance the motet shed multiple simultaneous texts in favor of a single sacred prose text and pervasive imitation among voices. Composers like Josquin des Prez, Palestrina, and Orlando di Lasso focused on clarity of text, balanced phrases, and carefully controlled dissonance. The motet became the quintessential medium for imitative counterpoint and expressive word‑painting in a liturgical or para‑liturgical context.

In the Baroque era the motet diversified: some traditions retained a cappella polyphony (e.g., Schütz), while others embraced basso continuo and concerted forces (French grand motet). In Lutheran Germany, the motet often engaged chorale melodies and set the stage for the sacred cantata. The genre continued into the Classical and Romantic eras as a vehicle for sacred choral craft, with composers like J.S. Bach (motets BWV 225–230) and later Bruckner contributing notable examples.

The motet’s techniques—cantus firmus treatment, imitation, voice leading, and text clarity—shaped nearly all subsequent Western choral music, informing the polyphonic mass, the madrigal’s contrapuntal style, and the Baroque cantata and oratorio.

Select a sacred Latin text (e.g., psalm verses, Marian antiphons) suitable for liturgical or devotional use. Write for 3–6 a cappella voices (SATB variants) or, for Baroque idioms, add basso continuo and occasional instrumental doubling.