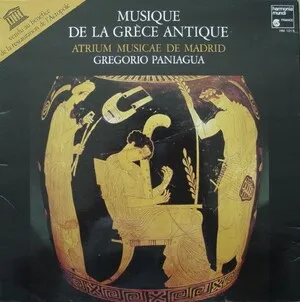

Ancient Greek music refers to the musical practices of the Greek world from the Archaic period through the Hellenistic and early Roman eras (roughly 8th century BCE to 3rd century CE). It was primarily monophonic, often performed by solo singer-instrumentalists or choruses, and closely tied to poetry, ritual, theater, and civic life.

Its sound world was shaped by modal systems (harmoniai), tetrachordal structures, and three genera (diatonic, chromatic, enharmonic), with tuning and intervallic ethos discussed by philosophers and theorists. Rhythm followed poetic meters (e.g., dactylic, iambic, paeonic), not modern bar-based accentuation. Instruments such as the lyre, kithara, and aulos dominated, with occasional percussion and later the hydraulis. Surviving notated fragments (e.g., the Seikilos epitaph, Euripides’ Orestes chorus, hymns by Mesomedes) and treatises (Aristoxenus, Aristides Quintilianus, Ptolemy) guide modern reconstructions.

Beyond entertainment, music framed worship (hymns and paeans), athletic and civic festivals, tragedy and comedy, and education. It profoundly shaped later Mediterranean liturgical chant and European music theory.

Ancient Greek music emerged in the Archaic period (c. 8th–6th centuries BCE), embedded in oral traditions that fused sung poetry with instrumental accompaniment. Music permeated ritual (hymns to gods), civic and athletic festivals (paeans, dithyrambs), symposium culture (skolia), and the theater (choral odes in tragedy and comedy). Professional kitharodes and aulodes performed alongside citizen choruses.

From early on, music carried ethical and affective power (ethos). Philosophers and theorists—Pythagoras (number and consonance), Plato (modes and education), Aristotle (catharsis), and later Aristoxenus—systematized pitch into tetrachords and harmoniai (Dorian, Phrygian, Lydian, etc.), distinguished genera (diatonic, chromatic, enharmonic), and discussed tuning and melodic motion. Rhythm derived from poetic meters rather than fixed bar accents. The music was largely monophonic, with possible heterophonic embellishments in ensemble playing.

Core instruments included the lyre and kithara (plucked chordophones) for singers and virtuosi, and the double-reeded aulos for soloists and choruses. Percussion (tympanon, krotala) and, later, the hydraulis (water organ) supplemented certain contexts. Performance was situational: strophic lyric at symposia, grand choral formations in the orchestra of the theater, and competitive solo displays at festivals.

Two related notational systems (vocal and instrumental) used alphabetic symbols placed above text. Though only a few dozen fragments survive (e.g., Seikilos epitaph, Delphic hymns, Euripides’ Orestes), they confirm theories about modal organization and rhythm. Treatises by Aristoxenus, Ptolemy, and Aristides Quintilianus provide the most detailed theoretical frameworks.

The Hellenistic period saw stylistic expansion and virtuosity (e.g., Timotheus). Greek music heavily influenced Roman practice and, through Byzantine continuity, informed medieval Christian chant. Greek theoretical concepts (modes, tetrachords, tuning) migrated into Arabic and later Western theory, underpinning medieval modal systems and the intellectual foundations of Western classical music.