Melanesian music is an umbrella term for the traditional and contemporary sounds of the Melanesian region—principally Papua New Guinea, Solomon Islands, Vanuatu, Fiji, and New Caledonia.

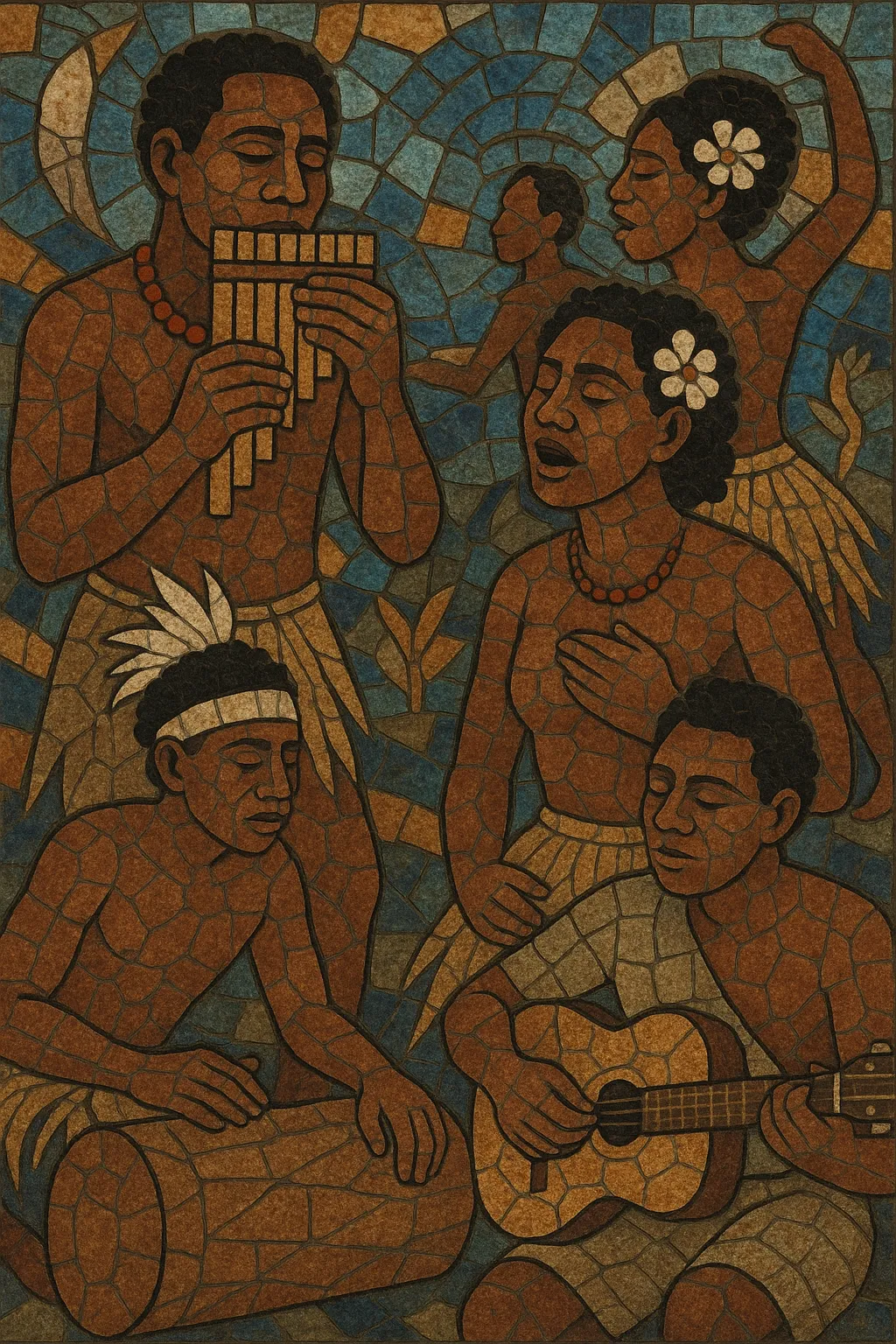

It blends deep-rooted indigenous practices (polyphonic choral singing, panpipes, log drums, bamboo ensembles, conch shells, dances tied to ceremony and land) with influences introduced through missionization and global media (Christian hymnody, string-band guitar/ukulele, country, and later reggae/dancehall grooves). Vocal harmony—often in rich, close parts—call-and-response, and cyclical, dance-centered rhythms are core features, while lyrics move between local languages and lingua francas like Tok Pisin, Bislama, and Pijin.

Contemporary Melanesian pop includes string-band ballads, island-reggae fusions, kaneka (New Caledonia), and Fijian vude, yet it retains a communal, participatory ethos that foregrounds kinship, kastom (custom), and connection to place.

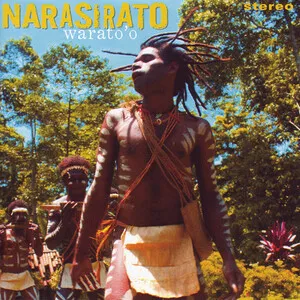

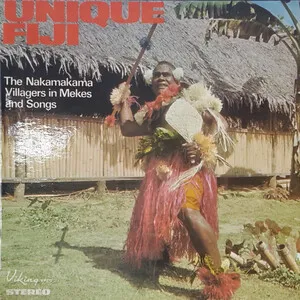

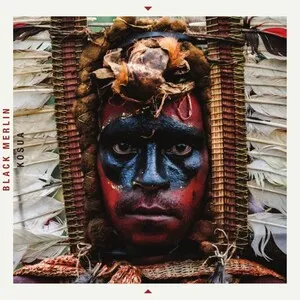

Melanesian music predates written history and is inseparable from social life, ceremony, and the natural environment. Core practices include multipart choral singing, call-and-response, and polyrhythmic percussion using slit-log drums (garamut), stamping tubes, rattles, handclaps, and body percussion. Instrumental traditions vary by island: the ‘Are’are panpipes of the Solomon Islands, bamboo ensembles in Vanuatu and PNG, and conch shell signaling are emblematic. Music encodes genealogies, land rights, and ritual knowledge, with performance embedded in dance and visual adornment.

The arrival of missionaries and colonial administrations brought Christian hymnody, European harmony, and new instruments (guitars, ukuleles, accordion). Indigenous singers rapidly localized hymns, developing distinctive village choirs whose close harmonies and local languages became a hallmark across Melanesia. Early “string band” formations—guitars, ukulele, bass or tea-chest bass, light percussion—arose as community dance music, absorbing waltz and polka rhythms alongside local grooves.

Radio, cassettes, and inter-island travel fueled a regional exchange. String-band styles flourished in PNG, Solomon Islands, and Vanuatu, while in Fiji the danceable vude emerged by blending meke rhythms with disco, rock, and pop. In New Caledonia, kaneka grew as a modern Kanak idiom, uniting traditional vocal textures with electric bands as a vehicle for cultural affirmation. These decades coincide with independence movements and rising urban centers, where popular music became a site of identity and political expression.

From the 1990s onward, reggae and dancehall rhythms strongly shaped Melanesian pop (often dubbed “island reggae”), without displacing choral and string-band roots. Artists fuse one-drop grooves with local languages, choir-like backing vocals, and guitar-led textures. Scene-specific currents—kaneka (New Caledonia), contemporary string band and kastom-infused fusions (Vanuatu, PNG, Solomons), and Fijian vude/pop—coexist and cross-pollinate. Digital production and social media have widened the audience, while community performance, church choirs, and ceremonial music continue to anchor musical life.