Hymns are strophic, text-driven songs of praise, devotion, or instruction intended for congregational or communal singing, most closely associated with Christian worship. They typically use clear, memorable melodies, regular poetic meters, and straightforward harmonies so that large groups can sing together with ease.

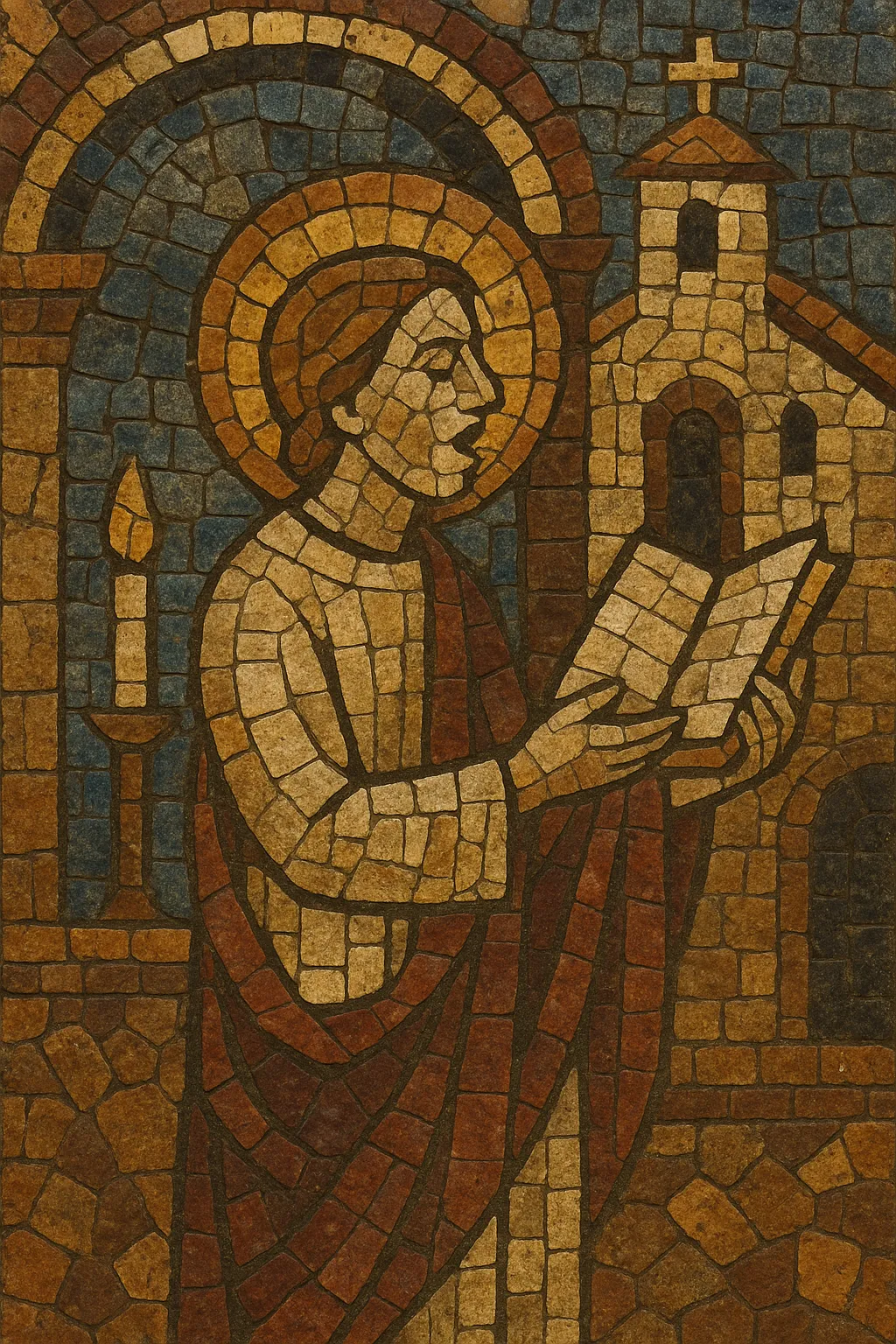

While the concept of a hymn as a sacred song predates Christianity (e.g., in Ancient Greek and Jewish traditions), Christian hymnody coalesced late in the 4th century with Ambrosian practice in Milan and then expanded through Latin and Greek liturgical cultures. Over time, hymn singing moved from monastic and cathedral settings into congregational life, especially after the Protestant Reformation, where metrical psalms and vernacular hymns became a defining feature of worship.

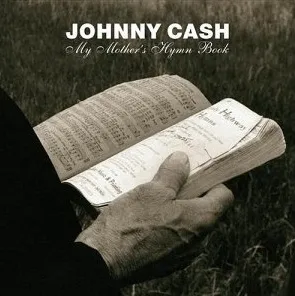

Modern hymnody ranges from chant-like, modal melodies without accompaniment to robust, four-part chorale harmonizations with organ, and even contemporary arrangements that adapt classic hymn texts and tunes to newer popular styles.

Hymns are sacred songs designed for communal singing. In Christian contexts, they function as praise, confession, catechesis, and prayer in poetic form, set to singable tunes. Their development bridges ancient chant traditions and later congregational song.