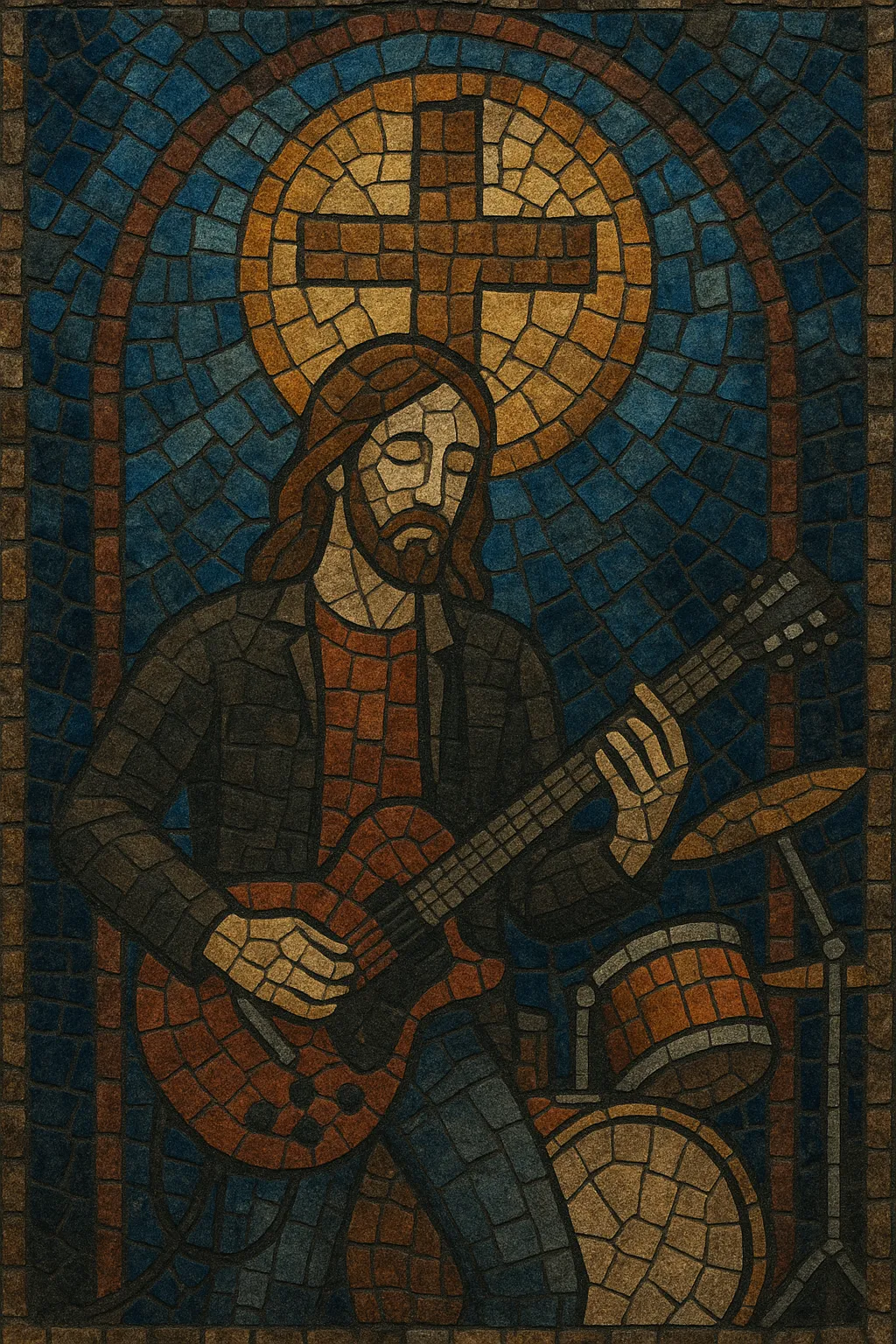

Christian rock is a family of rock styles whose lyrics and outlook are explicitly Christian, ranging from evangelistic and testimonial songs to social commentary filtered through a Christian worldview.

Musically, it spans the same breadth as mainstream rock—soft rock ballads, heartland and country-tinged rock, pop-rock, alternative, hard rock, and even metal—while keeping melodies and hooks accessible for radio and congregational settings. Typical instrumentation includes electric guitars, bass, drums, and keyboards, with production that varies from raw garage energy to polished arena-sized anthems.

The genre coalesced out of the late-1960s Jesus movement and the early-1970s "Jesus music" scene, later developing a robust industry of labels, radio, and festivals. While purpose-driven in its message, Christian rock has produced artists who crossed into the mainstream and influenced modern worship’s arena-rock sound.

Christian rock emerged from the U.S. Jesus movement, where countercultural folk and rock musicians began writing explicitly Christian lyrics. The period’s “Jesus music” (coffeehouse circuits, church basements, and indie presses) laid the foundation, with pioneers like Larry Norman presenting rock idioms as a vehicle for evangelism and social critique.

By the 1980s, dedicated labels, retailers, and radio formats coalesced around Contemporary Christian Music (CCM). Bands such as Petra professionalized touring and production, while Stryper brought glam-metal aesthetics to faith-centered lyrics, expanding Christian rock’s stylistic range and youth appeal.

The 1990s saw strong mainstream crossovers: dc Talk fused rock with hip hop and pop; Jars of Clay and Newsboys found secular radio success; and Switchfoot later bridged mainstream alternative with faith-informed songwriting. Indie and punk-adjacent labels (e.g., Tooth & Nail and Solid State) fostered alternative, emo, and heavier variants, while festivals like Cornerstone became hubs for subcultural exchange.

Christian rock continues across multiple substyles—from radio-friendly pop-rock to post-grunge and hard rock—while significantly shaping modern worship’s arena-ready sound (big choruses, atmospheric guitars). Digital platforms widened global reach and enabled regional scenes, and many artists now operate fluidly between worship contexts and general rock markets.

Use rock band basics: electric guitars (one rhythm, one lead), electric bass, drum kit, and optionally keyboards/pads for atmosphere. For modern arrangements, add ambient/shimmer guitars and synth layers to widen the chorus.

Favor diatonic progressions with hooky, singable choruses. Common pop-rock progressions include I–V–vi–IV or vi–IV–I–V. Verses can be sparser (I–vi or IV–I motion) to leave space for lyrics. Melodies should be memorable and within comfortable vocal range; stacked harmonies reinforce big refrains.

Tempos typically range 90–140 BPM. Use straight-eighth feels for pop-rock and driving quarter-note kicks for anthemic choruses. For heavier tracks, employ drop-D power chords, palm muting, and dynamic build-ups (quiet verse → loud chorus).

Center lyrics on testimony, hope, grace, doubt-and-faith journeys, and scriptural allusions. Keep imagery concrete and relatable, avoiding jargon unless aimed at church settings. For congregational contexts, write inclusive, simple lines with clear theology and repeatable hooks.

Structure songs verse–pre–chorus–chorus–bridge–final chorus. Build dynamics across sections; use clean verses and layered, overdriven guitars in the chorus. Add delays/reverbs on lead lines for lift; gang vocals or octave doubles heighten climactic moments.