Austronesian music is an umbrella term for the diverse musical traditions of Austronesian-speaking peoples, whose homelands stretch from Taiwan through Island Southeast Asia to Oceania and Madagascar.

Across this vast region, common threads recur: strong communal vocal practices (call-and-response, responsorial choruses, and polyphonic or heterophonic textures), cyclic and interlocking rhythms, and an emphasis on idiophones and membranophones such as slit drums, gong-chime ensembles (e.g., gamelan and kulintang), and bamboo percussion. Melodies often favor anhemitonic pentatonic scales, limited ranges, and formulaic, chant-like contours, while dance and music are tightly integrated in ritual and social life (e.g., hula, siva, haka, and fatele).

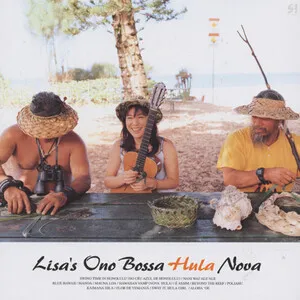

Local instrumentation and style vary widely—ukulele, slack-key guitar, and himene tarava in Polynesia; gong-row ensembles, kotekan interlocking, and metallophones in Indonesia; kulintang suites in the southern Philippines; nose flutes and bamboo zithers across the region; and valiha (tube zither) in Madagascar—yet they share maritime, oral-poetic, and communal aesthetics shaped by millennia of seafaring and exchange.

Archaeolinguistic and genetic evidence points to an Austronesian homeland in Taiwan, with maritime expansion beginning in the late Neolithic. While the music itself predates written records, core features—communal singing, anhemitonic pentatonic melody, oral poetry, and percussive idiophones—likely coalesced during this period and traveled along canoe-based trade and migration routes through Island Southeast Asia to Micronesia, Polynesia, and Madagascar.

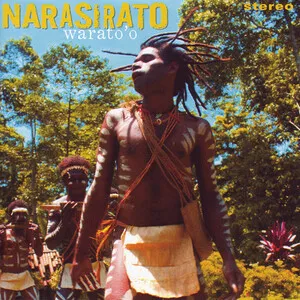

As communities settled new islands and coasts, distinct regional idioms emerged:

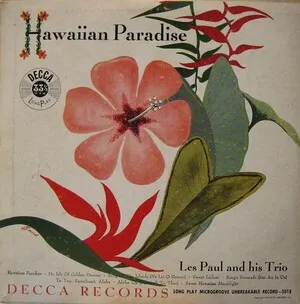

• Maritime Southeast Asia: Gong-chime ensembles (gamelan, kulintang), interlocking rhythms (kotekan), and metallophones became central in Java, Bali, and the southern Philippines. • Pacific: Chanted poetry (himene tarava), dance-music integration (hula, siva, haka), and new chordal instruments (e.g., ukulele’s ancestor, the Portuguese machete, adapted locally) reshaped performance. • Madagascar: The valiha tube zither and intricate guitar idioms blended Austronesian sensibilities with African influences.Colonial contact introduced guitars, hymnody, brass bands, and new harmonic practices. These interacted with indigenous cyclic forms, creating syncretic genres: Hawaiian hula ku‘i and slack-key, Polynesian choral styles, and hybrid village ensembles across Indonesia and the Philippines.

In the 20th century, nation-building and tourism prompted both stylization and revival. Folkloric troupes codified dance-song suites; urban artists fused indigenous rhythms with pop, reggae, and rock, birthing Pacific reggae and contemporary Polynesian pop. Since the 1990s–2000s, digitization and scholarship have foregrounded “Austronesian music” as a comparative framework, while indigenous artists lead language and cultural revitalization through recordings, festivals, and education.