Indigenous Taiwanese music encompasses the vocal and instrumental traditions of Taiwan’s Austronesian peoples (including Amis, Atayal, Paiwan, Bunun, Puyuma, Rukai, Tsou, Saisiyat, Tao/Yami, Thao, Truku/Seediq, and others).

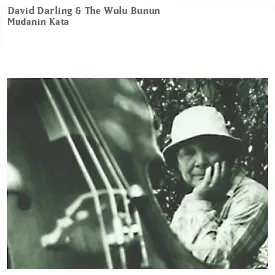

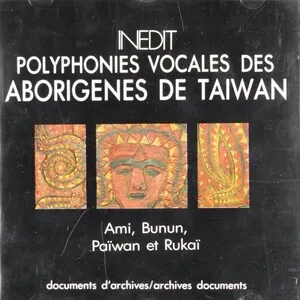

It is predominantly vocal-centric, featuring chant-like melodies, call-and-response, heterophony, and, in some communities, striking multi-part textures (for example, the Bunun’s famed polyphonic pasibut). Scales are often anhemitonic pentatonic or modal, and rhythms range from free, speech-like declamation in ritual contexts to lively festival meters supported by handclaps, stamping tubes, pestle-and-mortar percussion, and frame drums.

Common instruments include bamboo nose flutes (notably among Atayal and Paiwan), mouth harps/jew’s harps, bamboo stamping tubes, rattles, and shell or bamboo trumpets; instruments typically serve timbral and ritual functions rather than harmonic accompaniment. Lyrics are delivered in indigenous languages and center on communal life: millet cycles, seafaring, weaving, hunting, ancestral rites, and ecological knowledge.

While deeply rooted in precolonial practice, contemporary artists blend these idioms with pop, folk, and electronic production, carrying the traditions into modern stages and recordings.

Indigenous Taiwanese music predates written history, developing within Taiwan’s Austronesian communities as part of daily work, seasonal rites, and ancestor veneration. Vocal expression was primary, with ritual songs, work chants, and lullabies functioning as social memory and moral instruction. Instrumental sounds—nose flutes, mouth harps, rattles, and stamping tubes—accented ceremonies and dances rather than forming harmonic backdrops.

External records of these musics begin in the 1600s under Dutch and Spanish presence, later expanding during Qing rule. Missionaries and travelers noted distinctive multi-part singing (particularly among the Bunun) and the prevalence of pentatonic and modal chant. Oral transmission within clans remained the core of preservation and stylistic continuity.

Under Japanese rule, ethnographers produced early field recordings and transcriptions of "Takasago" (indigenous) groups. School systems introduced Japanese-language songs, but ritual and communal musics persisted in villages. Documentation during this period preserved invaluable audio snapshots of pre-war styles and repertoires.

After 1945, Sinicization policies and urban migration pressured indigenous languages and musics. Yet community rites—such as Saisiyat Pasta’ai ceremonies, Bunun malastapang gatherings, and Amis harvest festivals—sustained performance. From the 1970s–80s, scholars and cultural organizers began systematic fieldwork and local festivals, supporting intergenerational transmission.

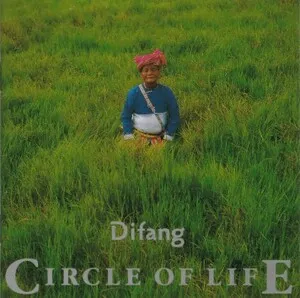

In the early 1990s, recordings by Amis singers Kuo Ying-nan (Difang) and Kuo Hsiu-chu (Igay) were sampled in Enigma’s "Return to Innocence," leading to a landmark authorship and rights case. The settlement brought international attention to indigenous Taiwanese singers and the ethics of sampling field recordings.

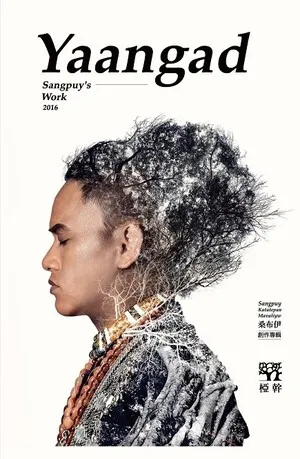

Since the 2000s, a vibrant cohort of indigenous artists has fused traditional vocal styles and languages with folk, pop, reggae, and electronic production. Acts like Sangpuy, Suming, Abao, and Ilid Kaolo have garnered major awards, while community ensembles continue to perform ritual music in situ. Today, indigenous Taiwanese music thrives both as living ceremony and as a contemporary creative force on world stages.

%2C%20Cover%20art.webp)