East Asian folk music is an umbrella term for the traditional, community-rooted musics of China, Japan, Korea, Mongolia, and related cultures in the region. While the practices themselves are ancient, the category coalesced in the 1900s as folklorists, broadcasters, and state ensembles began documenting, standardizing, and reviving rural and ritual repertoires.

Typical features include pentatonic-based melodies, flexible rhythm and meter, and heterophonic textures in which multiple performers ornament the same tune simultaneously. Vocal styles range from narrative epics and work songs to lyrical art-folk ballads, often delivered with regional timbres and rich ornamentation. Signature instruments include the Chinese erhu, pipa, dizi, and guzheng; the Japanese shamisen, shakuhachi, and koto; the Korean gayageum, haegeum, piri, and janggu; and Mongolian morin khuur and tovshuur, alongside various frame drums and gongs.

Beyond village and ritual contexts, East Asian folk music today thrives on stage and in media, influencing popular genres and fusions that retain traditional scales, storytelling, and timbral aesthetics.

The practices encompassed by East Asian folk music stretch back centuries, emerging from agrarian life, seasonal festivals, shamanic and Buddhist rituals, and court–village cultural exchange. Tunes and techniques were passed orally within families, guilds, and local troupes, producing a mosaic of regional song types (work songs, dance tunes, narrative epics) and distinctive instrumental idioms.

Over time, folk repertoires interacted with court and theatrical traditions (e.g., gagaku in Japan, local opera in China, and pansori and folk dance-drumming in Korea). Buddhist chant and Taoist ritual practice further shaped modal and melodic sensibilities, while itinerant bards and festival ensembles spread styles across trade routes, fostering shared pentatonic frameworks and heterophonic aesthetics.

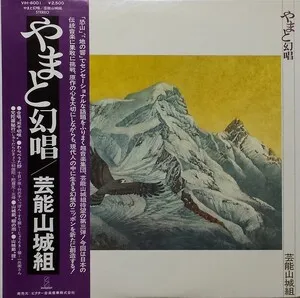

From the early 1900s, scholars, record labels, and later state cultural institutions began collecting, notating, and broadcasting folk music. This led to staged "folk" arrangements for concert ensembles, school curricula, and national festivals. Folk idioms also seeded popular forms like shidaiqu and kayōkyoku, and postwar urbanization inspired both nostalgic preservation and new hybrid expressions.

Since the late 20th century, traditional musicians and new-generation artists have blended folk instruments and modes with pop, rock, and electronic production. Pan-Asian and global collaborations, conservatory-trained performers, and grassroots revivalists have together kept regional styles vibrant while introducing them to international audiences.