Lisu music refers to the traditional and community-based musical practices of the Lisu people, an ethnolinguistic group centered in the Nujiang (Salween) river valleys of Yunnan in southwest China, with significant populations in northern Myanmar (Kachin State), northern Thailand, and parts of India.

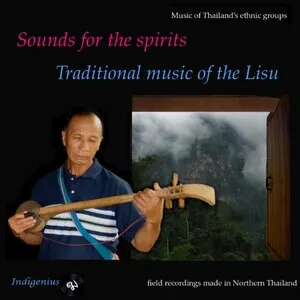

Characterized by pentatonic melodies, flexible heterophony, antiphonal (call-and-response) singing, and dance-oriented rhythms for festivals such as Kuoshi (Lisu New Year), the style spans solo ballads, courting songs, circle-dance repertories, narrative chant, and—since the early 20th century—vernacular Christian hymnody. Instruments commonly include bamboo flutes, jaw harps (kouxian), three-string lutes (sanxian-type), frame drums and clappers, and regionally adopted gourd free-reed pipes (e.g., hulusi). Vocal delivery features gentle portamento, narrow-range contours, and text-driven phrasing that foregrounds local language and poetic forms.

Lisu musical practice developed in the upland communities of the Nujiang river valleys over centuries, long before outside documentation. Core features—pentatonic melody, call-and-response singing, heterophonic ensemble textures, and circle-dance accompaniment—reflect broader East Asian folk idioms shaped by local language prosody, ritual cycles, and agrarian lifeways. Music functioned in courtship, seasonal festivals (notably Kuoshi), oral storytelling, and work contexts.

By the late 1800s and early 1900s, increased contact with Han Chinese, Yi, and Dai neighbors fostered repertoire and instrument exchange (e.g., bamboo flutes and gourd free-reed pipes). Mission activity—most famously through James O. Fraser’s work and the adoption of the Fraser Lisu alphabet—enabled the translation and indigenization of Christian hymns. This created a distinctive vernacular hymnody: four-part congregational singing merged with local melodic habits and Lisu text-setting, expanding the vocal tradition alongside enduring festival genres.

State-sponsored nationalities troupes in Yunnan began staging Lisu songs and dances, codifying costumes, choreography, and ensemble formats for stage and broadcast. Meanwhile, village-based practice remained vital, with elders, song leaders, and church choirs sustaining repertories. Cross-border Lisu communities in Myanmar and Thailand continued parallel traditions, often with church choirs as hubs for musical training. Today, Lisu music appears in cultural tourism, local radio, community recordings, and school programs, while fieldwork, archives, and regional folk ensembles help document and teach repertory. Contemporary performers blend traditional instruments with guitar or keyboard, record devotional music, and revitalize festival dance sets, maintaining stylistic hallmarks—pentatonic melody, antiphony, and community participation—across contexts.