East Asian classical music is an umbrella term for the literati, court, and religious art-music traditions of China, Japan, and Korea that crystallized during and after the Tang dynasty period.

It emphasizes timbral nuance, melodic ornamentation, and modal systems over Western-style harmonic progression. Textures are typically monophonic or heterophonic, with multiple instruments rendering the same melody in subtly varied ways.

Common materials include anhemitonic pentatonic scales (e.g., gong–shang–jue–zhi–yu in China), Japanese ryo/ritsu scales, and Korean pyeongjo/gyemyonjo modes. Rhythmic practice ranges from breath-based, rubato flow in solo traditions (e.g., guqin, shakuhachi) to highly codified cyclical patterns in court ensembles (e.g., gagaku, jeongak).

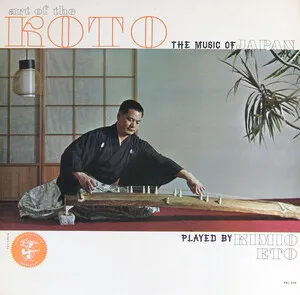

Iconic instruments include the guqin, pipa, erhu, dizi, and sheng (China); koto, shamisen, shakuhachi, hichiriki, ryuteki, and sho (Japan); and gayageum, geomungo, haegeum, daegeum, and piri (Korea). Performance aesthetics value restraint, subtle inflection, and a balance between rigorously codified repertoire and living, orally transmitted performance practice.

The foundations of East Asian classical music are closely tied to the Tang dynasty (7th–10th centuries), when Chinese court repertoires, ritual yayue, and instrument technologies spread across the region via diplomacy, migration, and the Silk Road. This period codified modal thinking, ensemble roles, and ceremonial functions that influenced Japan’s gagaku and Korea’s jeongak.

East Asian classical music served as sonic statecraft (ritual legitimacy in court rites), as meditative and didactic practice in Buddhist and Taoist contexts, and as refined self-cultivation among scholars. Repertoires often carried cosmological associations, ethical symbolism, and poetic allusions.

Colonial encounters, modernization, and nationalism reshaped institutions and instruments (e.g., concertized Chinese orchestras, conservatory systems). The 20th century saw documentation and revival of endangered repertoires, the creation of large traditional orchestras (guoyue), and new compositions that adapt classical idioms to contemporary concert life. Global recording and touring further disseminated these traditions, inspiring intercultural collaborations and historically informed performance.