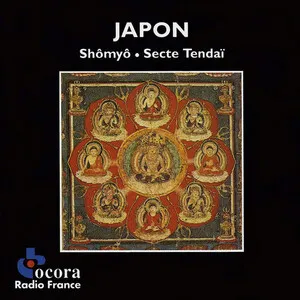

Shōmyō is the liturgical chant tradition of Japanese Buddhism, most closely associated with the Tendai and Shingon schools. The term (声明) literally means “voice and name,” reflecting its devotional function of vocalizing sacred names, sutras, and mantras.

Musically, shōmyō is predominantly monophonic and breath‑paced, with free rhythm, stepwise motion, and extended melismas. It draws on ancient East Asian modal thinking (e.g., ritsu and ryō pitch sets) and favors a narrow range, subtle inflection, and heterophonic unison when sung by a choir. Performances are typically a cappella, occasionally punctuated by small bells and gongs that cue entrances and sections.

The chant is performed in Japanese, Sino‑Japanese (kanbun), and mantric syllables (Siddham/Shittan). Its sound is solemn, spacious, and contemplative, designed to sanctify ritual space and guide collective meditation.

Shōmyō coalesced in Japan during the Nara (710–794) and Heian (794–1185) periods as Buddhism took root in court and temple life. Chant practices arrived via the continent—especially Tang‑dynasty China—and were adapted by Japanese monastics into a codified liturgy. Two principal lineages emerged: Tendai (centered on Mount Hiei’s Enryaku‑ji) and Shingon (centered on Mount Kōya and Kyoto), each curating its own repertories, modal nuances, and ritual functions.

Across the medieval era, temple schools formalized pedagogy, transmission, and notation (various shōmyō‑fu systems). Chant cycles were organized for calendrical rituals, memorials, and esoteric ceremonies. Although primarily unaccompanied, small bells and gongs were incorporated as temporal cues. The chant’s modal language and breath‑based pacing distinguished it from court music while sharing deep historical roots in East Asian theory.

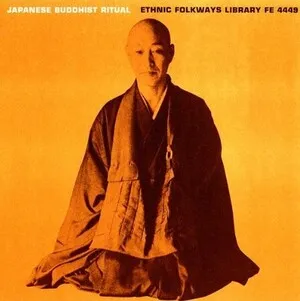

Shōmyō continued as living liturgy through the Edo period and into modern Japan, preserved in major temple complexes and monastic lineages. The 20th century brought audio documentation and concert presentations, helping to frame shōmyō as both sacred practice and intangible cultural heritage. Specialist ensembles and research groups (e.g., Tendai and Shingon shōmyō organizations) promoted study, recordings, and international tours.

In recent decades, shōmyō has appeared on concert stages and in collaborations with contemporary composers, sound artists, and ambient/minimalist contexts, while remaining central to temple ritual. Its spacious pacing, modal austerity, and collective unison continue to influence Japanese vocal aesthetics and inspire listeners beyond religious settings.