Ring shout is an African American sacred music-and-dance tradition rooted in the Gullah Geechee communities of the U.S. Southeast. It combines antiphonal (call-and-response) singing with a counterclockwise, shuffling ring dance, handclapping, and a percussive "shout stick" tapped on the floor.

Despite its name, the classic ring shout is not a shouted vocal style but a devotional ritual. A leader "calls" lines that a chorus answers, while "shouters" circle with restrained, gliding footwork (traditionally avoiding crossing the feet) and intensifying polyrhythms. The resulting texture fuses West and Central African communal dance practices with Christian spiritual texts, producing one of the oldest continuously practiced forms of African American sacred performance.

Ring shout emerged among enslaved Africans and their descendants in the Lowcountry of Georgia and South Carolina, especially on the Sea Islands. Drawing on West and Central African circle-dance ceremonies and call-and-response song, it took shape within clandestine "hush harbors" and later in praise houses, where Christian scripture and African aesthetics met.

By the mid-19th century observers were documenting the practice in the U.S. South, noting its counterclockwise ring, shuffling steps, and multipart polyrhythms produced by handclaps, foot patting, and the "shout stick." The ritual served as communal worship, spiritual catharsis, and cultural continuity under slavery and its aftermath.

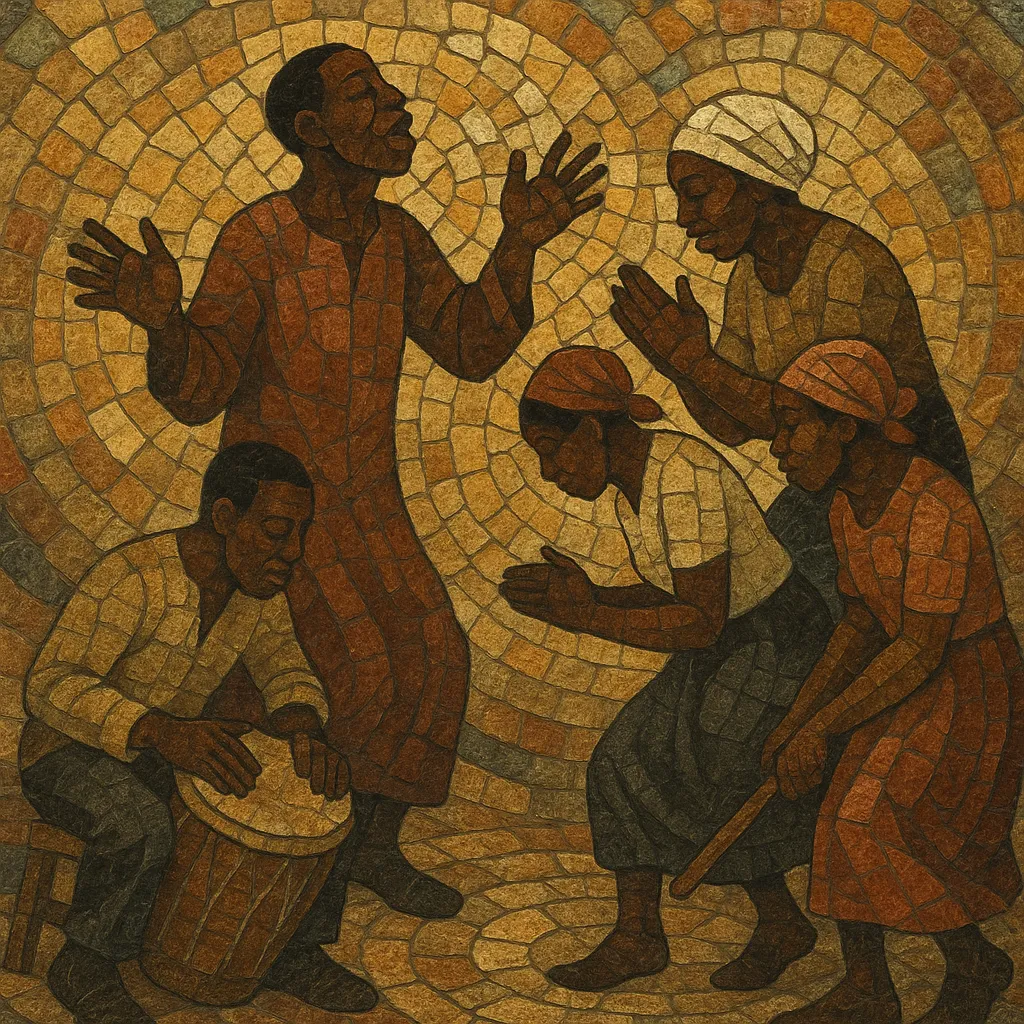

A typical ring shout involves four interlocking roles: a song leader (or "songster") who calls lines; "basers" who respond in chorus; a "sticker" who drives the beat with a wooden stick; and the ring of "shouters" who move in a tightening, shuffling counterclockwise circle. The performance builds through call-and-response verses, cycling refrains, and rising intensity until a climactic release.

After Emancipation, ring shouting persisted most strongly in Gullah Geechee communities, though urbanization and denominational shifts reduced its visibility. Folklorists and field recordists—later including Smithsonian Folkways releases—helped document the tradition.

From the late 20th century onward, ensembles such as the McIntosh County Shouters brought ring shout to concert stages and educational settings, catalyzing a revival. Today, the practice is recognized as a foundational African American sacred form that prefigured spirituals, gospel, and much of the call-and-response energy of later Black popular music.