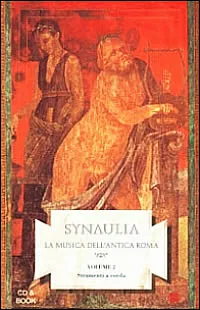

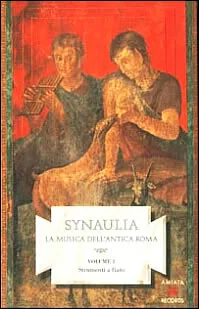

Ancient Roman music refers to the musical practices of the Roman Republic and Empire, roughly from the early centuries BCE through Late Antiquity. It was largely monophonic and orally transmitted, used in civic ritual, theater, private banquets, military life, and religious cults.

Its core sound world combined Greco-Roman string and wind instruments (cithara, lyre, tibia/aulos) with percussion (tympanum, cymbala, crotala, sistrum) and powerful brass (tuba, cornu, bucina). The hydraulis (water organ) added a distinctive timbre to spectacles. Rhythm often followed poetic meters, and performance likely favored heterophonic textures and ornamented melodic lines over harmonic progressions.

Rather than a single unified style, Roman music was a mosaic: theatrical and dance music for the ludi, refined kithara- and lyre-centered song for elite salons, processional and cultic soundscapes (including Egyptian-Isiac elements), and martial brass for command and ceremony.

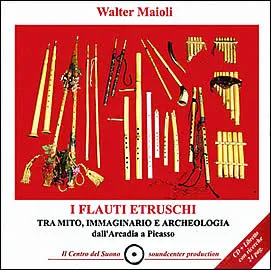

Roman music emerged within a cosmopolitan Mediterranean matrix. Early Italic and Etruscan practices were subsequently transformed by intensive Hellenistic (Greek) influence during the Republican period. By the 1st century CE, Greek instruments, modes, and pedagogies were standard among elite Roman musicians, while provincial and imported cults (e.g., Isis) contributed distinctive timbres and rituals (sistrum, frame drums).

Roman theory drew from Greek modal systems (harmoniai) and genera (diatonic, chromatic, enharmonic). Music aligned closely with poetic meters (iambic, trochaic, anapaestic), with likely flexible tempos, ornamentation, and heterophonic doubling. Notation was rarely used in performance contexts; instead, guilds, apprenticeships, and court ateliers sustained oral transmission.

As the Empire Christianized, theatrical and cultic repertoires waned while psalmodic chant rose. Roman performance practice—its modal thinking, oratorical pacing, and liturgical functions—fed into Old Roman chant and, indirectly, Western plainchant traditions. Martial brass practices foreshadowed ceremonial fanfare and march traditions in later European music.