Candomblé music is the sacred musical practice of the Afro-Brazilian religion Candomblé. It centers on polyrhythmic drumming ensembles, call-and-response singing, and dance that invites the presence (incorporation) of the orixás (divinities). The core ensemble features three hand-played atabaque drums (rum, rumpi, and lê), metal bells (agogô), and rattles/shakers (xequerê, adjá), with the lead drummer (alabê) cueing changes in rhythm and energy.

Stylistically, it preserves multiple West and Central African lineages—especially Yoruba (Ketu/Nagô), Fon/Ewe (Jeje), and Kongo/Angola—expressed in distinct toques (rhythmic patterns) such as ijexá, alujá, agueré, congo, and opanijé. Chants are performed in liturgical languages (predominantly Yoruba/Nagô, as well as Kikongo/Kimbundu and Fon) and in Portuguese, using a responsorial texture led by a solo cantor with a unison chorus. The music is not entertainment but ritual: every rhythm, melody, and text is tied to specific orixás, colors, dances, and ceremonial moments.

Beyond the terreiro (temple), Candomblé’s musical vocabulary has profoundly shaped Brazilian popular music, from afoxé and samba de roda to axé and MPB, especially through the diffusion of the ijexá timeline and call-and-response vocal aesthetics.

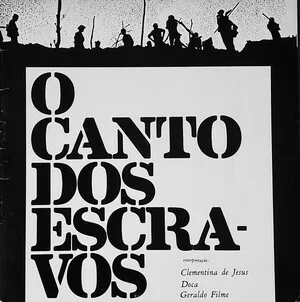

Candomblé music coalesced in Bahia during the 1800s among enslaved and freed Africans and their descendants. In the terreiros of Salvador and the Recôncavo, communities preserved and reorganized Yoruba (Ketu/Nagô), Jeje (Fon/Ewe), and Angola (Bantu) musical lineages. The ritual ensemble of atabaques (rum, rumpi, lê), agogô, and xequerê—along with responsorial chant in liturgical languages—formed a sonic system designed to serve the orixás through dance and spirit possession.

By the late 1800s and early 1900s, major houses such as Casa Branca, Gantois, and Ilê Axé Opô Afonjá codified repertories, drum tunings, and toques linked to particular deities and ritual moments. Despite this consolidation, practitioners faced police raids and legal restrictions that targeted African-derived religions. Nevertheless, terreiros maintained musical transmission orally, training alabês (lead drummers) and cantors who safeguarded ceremonial knowledge.

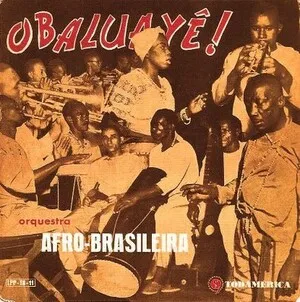

From the 1940s onward, ethnographers, photographers, and scholars—along with growing urban cultural pride—brought increased visibility. Candomblé’s rhythms, especially ijexá, radiated into public space via afoxé processions and later into samba-reggae, MPB, and axé. Recordings of liturgical chants and field documentation helped preserve house-specific styles and highlighted the musical role of revered priestesses and master drummers.

Today, Candomblé music remains a living ritual tradition taught within terreiros by lineage, with careful stewardship of sacred texts, rhythms, and dance. At the same time, its rhythmic language is ubiquitous in Brazilian music, and its aesthetics—polyrhythm, call-and-response, cyclical form, and timbral layering—are recognized worldwide as foundational to Brazil’s Afro-diasporic sound.

%20-%20Tam___%20Tam___%20Tam___!%2C%20Cover%20art.webp)