Arabic jazz is a fusion genre that blends the improvisational language, harmony, and ensemble practices of jazz with the modal (maqām) systems, microtonal inflections, and cyclical rhythms (iqāʿāt) of the Arab world.

Hallmark sounds include oud, ney, qanun, riqq, and darbuka playing alongside a jazz rhythm section of double bass, drum set, piano, and horns. Melodies often trace maqām pathways (Hijaz, Rast, Nahawand, Bayati, Saba, etc.), while grooves alternate between swing and straight, odd-meter cycles such as samāʿī thaqīl (10/8) or malfūf (2/4), and 4/4 patterns like maqṣūm. Harmonically, arrangements favor modal drones, pedal points, suspended voicings, and selective use of jazz extensions, allowing maqām-centric melodies and taqsīm-style improvisation to stay prominent.

The result is a sound that can be contemplative and spacious or propulsive and danceable, maintaining the narrative arc of maqām development while embracing jazz’s call-and-response, risk-taking solos, and ensemble interplay.

Arabic jazz took recognizable shape in the late 1950s, notably through American bassist and oud player Ahmed Abdul-Malik, whose recordings (e.g., Jazz Sahara, 1958) brought maqām-informed melodies and Middle Eastern percussion into a small‑group jazz context. These early experiments aligned naturally with jazz’s growing modal turn, creating fertile ground for cross‑cultural improvisation.

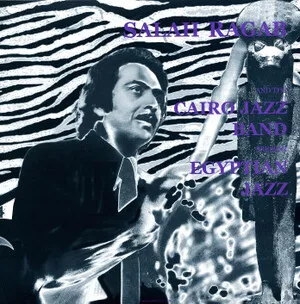

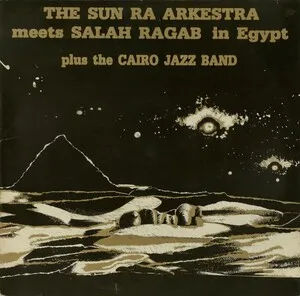

In the 1960s, Egyptian drummer and bandleader Salah Ragab established the Cairo Jazz Band, composing pieces that drew on Egyptian rhythmic cells and melodic modes within big‑band and small‑ensemble jazz formats. Parallel projects in the Levant and North Africa explored similar paths, integrating Arabic instruments and forms (samāʿī, bashraf-like frameworks) with jazz arranging and improvisation.

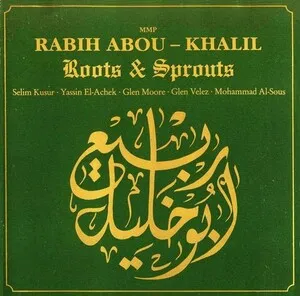

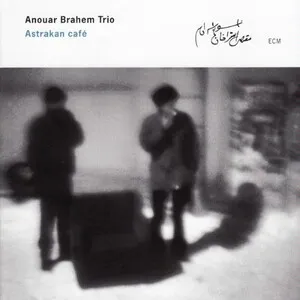

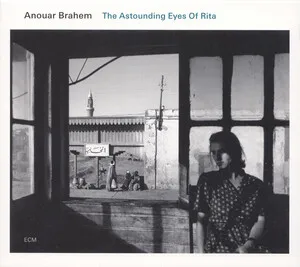

Civil conflicts and broader migration patterns helped spread the music via the Arab diaspora. In Lebanon, Ziad Rahbani injected jazz harmonies and grooves into theatre music and pop, while ECM-associated artists such as Rabih Abou‑Khalil and Anouar Brahem framed oud-led ensembles in chamber‑jazz settings. This period crystallized Arabic jazz’s modal identity, balancing maqām development with contemporary jazz timbres.

The 21st century has seen wide international visibility. Artists like Dhafer Youssef, Ibrahim Maalouf, Yazz Ahmed, Tarek Yamani, and Omer Avital advanced microtonal techniques (e.g., quarter‑tone trumpet), hybrid grooves, and sophisticated orchestration. Festivals and labels worldwide now program Arabic jazz regularly, and the style informs nu‑jazz, world‑jazz, and cross‑genre collaborations. While aesthetics vary—from contemplative, ECM‑like textures to hard‑grooving ensembles—the core remains maqām-centric melody, Arabic rhythmic cycles, and jazz improvisational practice.

%2C%20Cover%20art.webp)