Your digging level

Description

Bosnian folk music is the traditional music of Bosnia and Herzegovina, spanning urban salon songs and rural village styles. Its best-known urban form is sevdalinka (sevdah), characterized by ornate, melismatic singing, modal (makam-derived) melodies, and intimate, poetic lyrics about love, longing, and everyday life under Ottoman influence.

Alongside sevdalinka are rural styles from different regions, including close-harmony shout-singing such as ganga (common in western Herzegovina), narrative epic song with gusle-like aesthetics (today often performed on šargija/saz or accordion), and lively kolo dance tunes. Over time, instruments such as saz/šargija, tamburica, violin, accordion, and later guitar and light percussion came to accompany these songs, with modern arrangements sometimes adding small ensembles. The result is a repertoire that can feel both deeply melancholic and gently festive, interweaving Ottoman-era modal flavor with South Slavic folk poetics.

History

Bosnian folk music took on its distinctive character during the Ottoman period, when urban song traditions blossomed in Bosnian towns. Sevdalinka emerged in this milieu, melding South Slavic verse with Ottoman makam aesthetics and salon performance culture. The saz/šargija became a key accompanying instrument, while songs circulated orally across households, courtyards, and coffeehouses.

After 1878, urbanization and new media (print, early recordings) helped codify lyrics and melodic variants. Western instruments (violin, tamburica, later accordion) entered ensembles, and some repertoires adopted more regular meters, though the rubato, improvisatory vocal style of sevdah remained central.

Radio Sarajevo, state folk festivals, and labels like Diskoton professionalized and popularized Bosnian folk. Beloved interpreters including Safet Isović, Himzo Polovina, Zaim Imamović, Nada Mamula, Zehra Deović, and Beba Selimović standardized canonical versions while preserving modal nuance. Rural forms (ganga, narrative songs, kolo tunes) coexisted with urbane sevdalinka, and the accordion became a principal instrument.

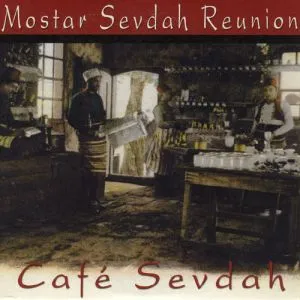

Following the 1990s war, a revival anchored by artists and ensembles such as Mostar Sevdah Reunion, Amira Medunjanin, Hanka Paldum, and Božo Vrećo brought sevdah and broader Bosnian folk to international stages. Contemporary recordings often blend traditional vocal ornamentation with chamber, jazz, or world-fusion textures, maintaining the genre’s core melancholy and poetic intimacy while reaching new audiences.