Your digging level

Description

Sephardic music is the song and liturgical tradition of the Sephardic Jews—descendants of the Jewish communities of medieval Iberia—carried and reshaped across the Mediterranean after the 1492 expulsion from Spain. It encompasses both secular Judeo‑Spanish (Ladino) repertories of romances, kantikas, and life‑cycle songs, and sacred Hebrew piyyutim set to modal melodies.

Musically it blends medieval Iberian balladry with the modal systems and rhythmic cycles of the Ottoman, Maghrebi, and Balkan worlds. Melodies often use maqam-like modes (e.g., Hijaz/Phrygian dominant, Bayat, Nahawand), asymmetrical “aksak” meters (7/8, 9/8, 10/8), and ornamented, melismatic vocal lines. Typical instruments include oud, qanun, violin, guitar, clarinet, and frame drums such as riq, bendir, and daf, with textures that are primarily monophonic or heterophonic rather than harmonically driven.

History

Sephardic song took shape among the Jewish communities of medieval Spain and Portugal, where Hebrew liturgical poetry (piyyut) coexisted with secular Judeo‑Spanish (later called Ladino) songs. The secular repertory drew on Iberian ballad traditions (romances) and courtly song forms, while sacred music reflected the modal contours and cantillation habits of Jewish worship.

Following the 1492 expulsion from Spain and 1497 from Portugal, Sephardim dispersed across the Ottoman Empire (e.g., Istanbul, Salonika, Sarajevo, Izmir), North Africa (e.g., Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia), and Mediterranean port cities. In these locales the music absorbed Ottoman/Turkish classical modes and usul, Balkan asymmetrical meters, and Maghrebi rhythmic feels. Distinct dialects and sub‑styles emerged, including Eastern Sephardic Ladino and North African Haketia traditions.

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, Sephardic repertories circulated through cafés, salons, synagogues, and family life‑cycle events. Early commercial recordings captured canonical performers such as Haim Effendi in Istanbul. Printed songbooks and field collections began to codify texts and melodies even as communities faced assimilation, war, and migration.

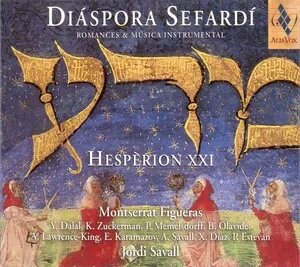

Scholars, cantors, and collectors (notably Yitzhak Levy) documented romances, kantikas, and sacred melodies in Israel and the diaspora. From the late 20th century, early‑music and world‑music artists (e.g., Jordi Savall, Savina Yannatou, Yasmin Levy) revitalized the repertoire on international stages. Today, performers compose new Ladino songs, pair traditional modes with contemporary harmony, and collaborate across Mediterranean, Middle Eastern, and global genres while community ensembles and cultural institutions sustain local traditions.

How to make a track in this genre

Decide whether you are writing a secular Ladino kantika/romance (often strophic, narrative, and danceable) or a sacred Hebrew piyyut (more cantorial, sometimes freer rhythm). For North African flavors, consider Haketia (Judeo‑Spanish of Morocco); for Eastern traditions, use Ladino with Ottoman/Turkish or Balkan contours.

Select a maqam‑like mode (e.g., Hijaz/Phrygian dominant for a bittersweet color, Bayat for warmth, Nahawand for minor tonality). Keep the melody central, with narrow to moderate ranges and stepwise motion, and add melismas, mordents, and slides at cadences. If using fixed‑pitch Western instruments, approximate microtonal inflections tastefully.

Use characteristic meters: 9/8 (karsilama, often grouped 2+2+2+3), 7/8 (3+2+2), 10/8 (samai thaqil), or lilting 6/8 for lullabies and processional songs. Percussion such as riq, bendir, daf, and darbuka should articulate cycles with light, danceable patterns; handclaps (palmas) or group refrains can energize the texture.

Favor monophony or gentle heterophony—multiple instruments doubling and embellishing the tune. Keep harmony sparse: drones, open fifths, and occasional modal pedal points support the melody. Avoid heavy functional progressions; when harmonizing, use parallel thirds/sixths and modal cadences that respect the scale’s characteristic degrees.

Write strophic verses with a recurring estribillo (refrain). For romances, aim for octosyllabic lines with assonant rhyme on even lines. Themes commonly include love, exile, weddings, lullabies (e.g., “Nani, nani”), and moral tales. For piyyutim, preserve poetic acrostics and align melodic phrasing with liturgical text accents.

Combine oud, qanun, violin/viola, guitar, clarinet/shawm (zurna for color), and frame drums; add kanun or ney for Ottoman hues, or guitar/mandolin for Iberian touches. Begin with a solo vocal line (a cappella or over a drone), then add counter‑melodies and percussion. End with a communal refrain, allowing call‑and‑response between soloist and chorus.

Top albums