Asian music is an umbrella term for the diverse traditional, classical, and folk musical systems of the Asian continent, spanning West Asia (the Middle East), South Asia, Central Asia, East Asia, and Southeast Asia.

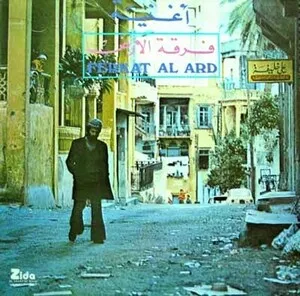

Across regions, it often privileges modal thinking over functional harmony, uses non‑equal temperaments and microtones, favors heterophonic textures, and emphasizes ornamentation, melisma, and timbral nuance. Signature frameworks include raga and tala in South Asia, maqam and usul in West Asia, gagaku and shōmyō in Japan, yayue and sizhu in China, yayue-derived court lineages in Korea and Vietnam, and gong‑chime orchestras (gamelan, pinpeat) in Southeast Asia. Instruments such as sitar, sarod, erhu, pipa, guqin, koto, shamisen, gayageum, qin, oud, ney, kanun, duduk, morin khuur, and extensive families of gongs and drums define its soundworlds.

While heterogeneous, Asian musical cultures share historical interconnections via the Silk Roads, religion (Buddhist, Hindu, Islamic, Daoist, Confucian contexts), court patronage, and oral pedagogy. In modern times, these traditions have inspired popular styles, film music, worldbeat, and experimental and ambient practices worldwide.

Asian musical lineages stretch back millennia, with early court and ritual systems documented in China (yayue), Vedic chant in South Asia, and modal practices that later inform Persian dastgāh and Arabic maqām in West Asia. East Asia developed court repertoires (gagaku in Japan, aak in Korea) and vocal liturgies (shōmyō, Buddhist chant), while Southeast Asia cultivated gong‑chime orchestras that codified cyclical time.

From antiquity through the medieval era, the Silk Roads enabled exchange of instruments (lutes, flutes, bowed strings), scales, and aesthetics among West, Central, South, and East Asia. Ideas of modality, rhythmic cycles, and ornamentation circulated widely, producing families of related practices (e.g., maqām, raga) adapted to local poetics and performance contexts.

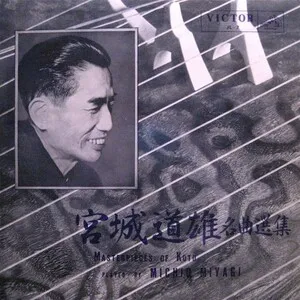

Courtly and devotional patronage sustained elite traditions alongside vibrant folk forms. Print culture, pedagogy, and palace ensembles preserved repertories, even as urban popular musics (shidaiqu in China, enka/ryūkōka in Japan, Ottoman/Turkish classical continuities) began blending traditional modalities with new instruments and forms.

Recording, radio, and cinema amplified Asian musics—Bollywood and filmi in India; kayōkyoku, later J‑Pop, in Japan; Cantopop/Mandopop in Chinese‑speaking regions; and diverse West Asian popular styles. Art music modernists and revivalists formalized pedagogy, ensembles, and conservatories, while diasporas and intercultural collaborations broadened reach.

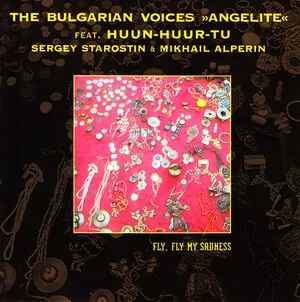

Today, Asian music informs worldbeat, ambient/new age, experimental and minimalist composition, pop idol industries (K‑Pop, J‑Pop, Mandopop), and global club cultures. Heritage traditions remain vital, taught through oral and institutional means, and continue to inspire cross‑genre works that retain core modal and rhythmic sensibilities.

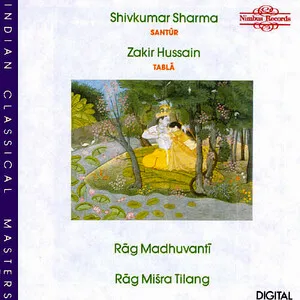

Decide on a mode system appropriate to the subregion: raga (South Asia), maqam (West Asia), pentatonic or heptatonic modes (East Asia), or pelog/slendro (Southeast Asia). Treat the mode as a vocabulary of characteristic tones, microtonal inflections, and signature phrases rather than a mere scale.

Use cyclical meters (tala/usul) or colotomic structures (gamelan) to articulate form. Mark structural accents with drums or gongs, and let improvisation unfold within the cycle.

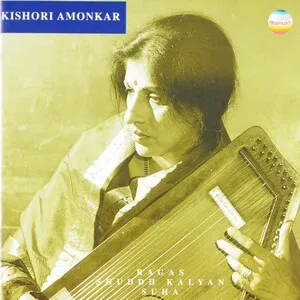

Prioritize expressive ornaments—gamak, meend (glides), mordents, grace notes, vibrato—and melismatic vocal lines. Employ drones (tambura, shruti box) or sustained tones to establish modal center.

Favor heterophony: multiple instruments render the same melody with individualized ornamentation. Combine regional instruments (e.g., sitar/tabla, oud/ney, erhu/pipa, koto/shakuhachi, gamelan metallophones) with voice; if fusing with modern production, preserve timbral identity and modal intonation.

Structure performances with an unmetered introduction (alap/taqsim/jō) to reveal the mode, followed by metered sections increasing in density and speed. Integrate call-and-response, poetic stanzas, or dance-gesture cues where culturally relevant.

Align text with traditional forms (ghazal, devotional poetry, courtly verse) and languages. Emphasize imagery, spirituality, and emotional nuance; allow the prosody to guide rhythmic placement.

Avoid forcing equal temperament; use pitch-bend and fine-tuning for microtones. Record close, detailed timbres to capture transient nuance. In hybrids, let traditional percussion or gongs define the groove, layering modern bass/harmony subtly around the modal core.