Your digging level

Description

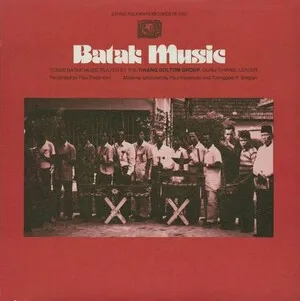

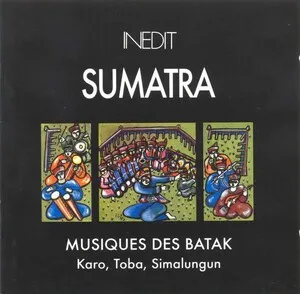

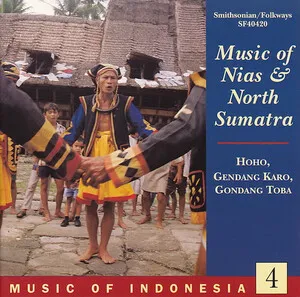

Batak music refers to the traditional and modern musical practices of the Batak peoples of North Sumatra, Indonesia, including Toba, Karo, Simalungun, Pakpak/Dairi, Angkola, and Mandailing communities.

It features distinctive gong-and-drum ensembles for ceremonies and social dances (tortor), most famously the Toba gondang sabangunan (with taganing drums, gordang bass drum, ogung gongs, sarune shawm, and hesek timekeeper) and the Mandailing gordang sambilan (nine large tuned drums). A contrasting chamber-like setup, the gondang hasapi ensemble, centers a two-stringed lute (hasapi) with xylophone (garantung) and bamboo flute (sulim), producing lyrical, heterophonic textures.

Alongside ritual music, Batak communities developed a powerful choral tradition under Christian influence, and since the mid-20th century a lively Batak pop repertoire emerged, blending traditional melodies and poetic forms with Western harmony and instrumentation.

History

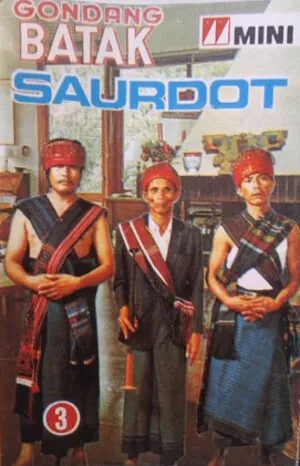

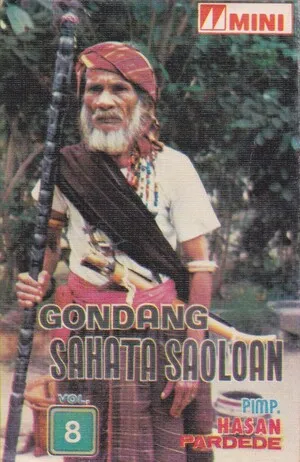

Batak musical traditions long predate written records, serving as sonic anchors for rites of passage, clan gatherings, and communal dance (tortor). Each Batak subgroup maintains a characteristic ensemble and repertoire. The Toba gondang sabangunan accompanies life-cycle ceremonies, while the Mandailing gordang sambilan is central to noble and community rites. Repertoires are organized as sequences (gondang) requested by hosts and elders to mark stages of a ritual.

Ensembles combine drums and knobbed gongs with a penetrating double-reed shawm (sarune) and a timekeeping idiophone (hesek). The gondang hasapi ensemble emphasizes a two‑stringed lute (hasapi) with wooden xylophone (garantung) and bamboo flute (sulim), producing flowing heterophony, supple ostinati, and ornamental melodic lines. Modal systems and non-tempered tunings reflect local aesthetics rather than Western equal temperament.

From the mid‑1800s, Protestant missionization fostered hymn-singing and part-writing in Batak languages. Local composers began crafting new songs that blended indigenous melody with Western harmony and strophic forms. Radio and recording in the 20th century circulated these songs across Sumatra and the Indonesian archipelago.

Post‑independence, Batak musicians recorded cassettes and performed in urban centers like Medan and Jakarta. Pop Batak incorporated electric instruments, keyboard, and Western chord progressions while retaining Batak lyrics and melodic turns. Since the 2000s, arrangers and bands have revitalized traditional pieces for the stage and world‑music festivals, and regional governments have recognized iconic practices (e.g., gordang sambilan) as intangible cultural heritage.

Modern ensembles alternate between ceremonial functions and concert formats, while choirs, pop trios, and fusion bands connect diaspora communities. Educational programs and cultural institutions support transmission, ensuring ritual repertories and instruments remain active alongside evolving studio productions.