Indonesian music is an umbrella term for the vast and diverse musical traditions found across the Indonesian archipelago, spanning thousands of islands and hundreds of ethnic groups. It encompasses ancient courtly gamelan traditions of Java and Bali, regional folk idioms of Sumatra, Sulawesi, Kalimantan, and Nusa Tenggara, and modern popular styles like dangdut, pop Indo, rock, hip hop, and electronic hybrids.

Its traditional backbone features tuned percussion ensembles (gamelan) organized around cyclical, colotomic structures and pentatonic tuning systems (sléndro and pélog). Instruments such as saron, bonang, gender, gong ageng, kendang, rebab, suling, kacapi, and sasando shape distinctive timbres and interlocking patterns. Islamic recitational aesthetics, Malay song forms, Indian film and classical music, Arabic maqāmic practice, and Western classical and popular music all contribute to Indonesia’s modern soundscape.

In the 20th century, colonial contact, radio, recording technologies, and urban migration catalyzed hybrid genres (e.g., keroncong, gambus/orkes gambus). After independence (1945), mass media, cassettes, and TV helped consolidate a national market, elevating styles like dangdut and pop Indonesia, while regional languages and forms (e.g., jaipongan, campursari) remained vibrant and influential.

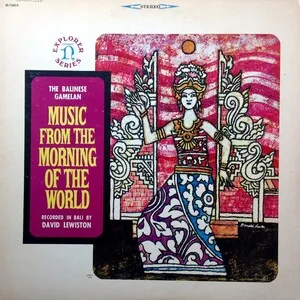

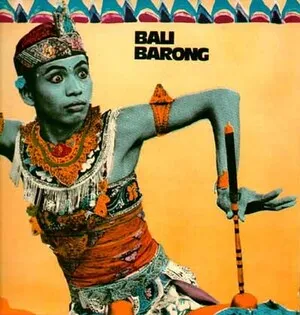

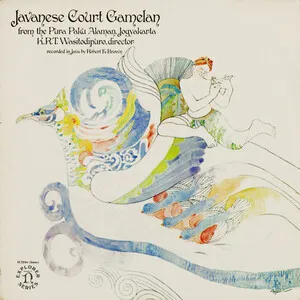

Long before the modern nation-state, Indonesian musical cultures thrived in courts, temples, and villages. Java and Bali developed sophisticated gamelan systems built on cyclical time, colotomic punctuation (gong cycles), and pentatonic tunings (sléndro, pélog). Elsewhere, distinct regional idioms—Minangkabau talempong, Batak vocal traditions, Dayak and Sasak musics, and eastern Indonesian string and gong ensembles—formed a mosaic of styles.

Under Dutch colonial rule, urban contact and maritime trade fostered syncretic genres. Keroncong emerged from Portuguese-influenced string music adapted to local aesthetics, while gambus/orkes gambus reflected Hadhrami-Arab influences filtered through Malay song. Western classical bands, military ensembles, and early recording/radio infrastructure widened musical exchange and audiences.

Nationhood spurred a shared cultural market. State radio (RRI), film, and later television amplified both traditional and modern sounds. Dangdut—blending Malay orkes, Hindustani film music, Arab maqāmic inflections, and local rhythms—rose to mass popularity (with figures like Rhoma Irama). Pop Indo and rock scenes blossomed (Koes Plus, later Slank and Dewa 19), while folk-protest voices (Iwan Fals) and regional fusions (jaipongan, campursari) kept local languages and idioms central.

Cassettes and VCDs gave way to MP3s, streaming, and social media, accelerating genre cross-pollination. Indie, metal, EDM, hip hop, and R&B flourished alongside evolving regional-pop hybrids (koplo/dangdut koplo, Sundanese and Javanese pop). Internationally visible artists (e.g., Anggun, Rich Brian, NIKI) signaled a confident global presence, while contemporary composers and producers recontextualize gamelan, kecapi-suling, and other traditions within modern pop and electronic frameworks.

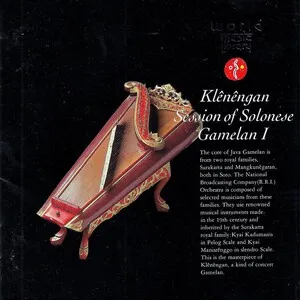

%20Orchestra%20-%20Kl%C3%AAn%C3%AAngan%20Session%20of%20Solonese%20Gam%C3%AAlan%20I%2C%20Cover%20art.webp)