Hindustani classical music is the North Indian classical tradition, built on the melodic framework of raga and the cyclical metric system of tala.

It emphasizes improvisation around a fixed composition (bandish for vocal, gat for instrumental), unfolding a raga’s characteristic ascent/descent (aroh–avroh), key tones (vadi–samvadi), signature phrases (pakad), and emotional color (rasa), often tied to time-of-day and seasonal associations.

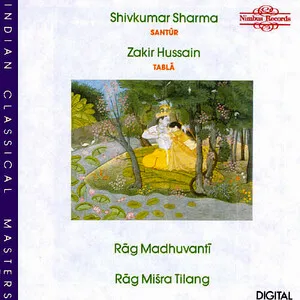

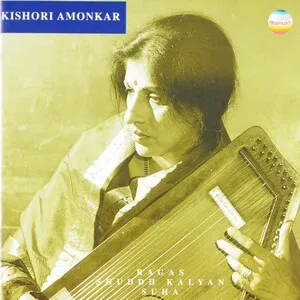

Core forms include dhrupad (austere and ancient), khayal (improvisation-rich and dominant today), thumri (lyrical and semi-classical), and instrumental idioms adapted for sitar, sarod, sarangi, bansuri, shehnai, and others. Rhythmic accompaniment centers on tabla (for khayal/thumri) or pakhawaj (for dhrupad), while a tanpura drone provides the tonal canvas.

Transmission traditionally occurs through gharanas (lineages) that preserve stylistic nuances in phrasing, ornamentation, and repertoire, while modern pedagogy and performance have broadened its reach globally.

Hindustani classical music traces its roots to ancient Indian musical thought, but it began to diverge distinctly from the southern Carnatic tradition during the medieval period. Courtly patronage under the Delhi Sultanate and early Mughal polities brought sustained interaction with Persian, Central Asian, and Islamic modal practices. Treatises like the 13th‑century Sangeet Ratnakara bridged older Sanskritic theory and evolving performance practice, while early dhrupad crystallized in temple and court contexts with pakhawaj accompaniment.

Under the Mughal emperor Akbar, legendary musician Miyan Tansen and contemporaries shaped a robust court culture: codifying ragas, expanding dhrupad, and influencing instrumental idioms. This era saw deeper synthesis of indigenous raga grammar with Persianate aesthetics and devotional currents (Hindu bhakti and Sufi). The result was a refined art that balanced austere alap explorations with measured composition and rhythmic sophistication.

Khayal rose to prominence, foregrounding elastic improvisation (vistaar), virtuosic taans, and varied rhythmic play (bol‑bant). Patronage shifted from imperial courts to regional princely states, fostering gharanas (lineages) such as Gwalior, Agra, Jaipur–Atrauli, Kirana, and Patiala. Semi‑classical forms like thumri thrived in cultural centers like Lucknow and Benares, while instruments such as sitar, sarod, and sarangi developed distinctive concert traditions.

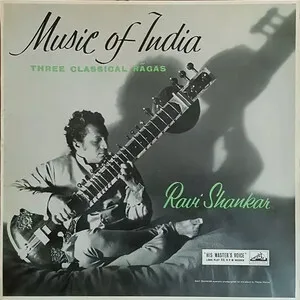

Musicologists Vishnu Narayan Bhatkhande and Vishnu Digambar Paluskar advanced pedagogy, notation, and public concert culture. All India Radio standardized raga presentation and expanded audiences. Maestros including Bade Ghulam Ali Khan, Bhimsen Joshi, Ravi Shankar, Ali Akbar Khan, Vilayat Khan, and Bismillah Khan brought the music to global stages, influencing jazz, rock, and world fusion.

Recordings, festivals, and conservatories spread Hindustani music worldwide. While gharana identities persist, artists freely blend approaches, collaborate across genres, and use new media. Dhrupad has seen a revival, khayal remains central, and instrumental virtuosity continues to evolve, all while the raga–tala core and time‑of‑day aesthetics stay intact.

Start by selecting a raga with clear aroh–avroh (ascent/descent), pakad (signature motif), vadi–samvadi (primary/secondary tones), and associated time‑of‑day or seasonal context. Pair it with a tala (e.g., Teentaal 16 beats, Ektaal 12, Jhaptaal 10, Rupak 7) and a tempo plan (vilambit → madhya → drut) suited to the form.

Tune to the tonic (Sa) and establish a continuous tanpura drone to define the harmonic field. Ensure intonation (shruti) and just‑intoned intervals fit the raga’s microtonal inflections and resting points (nyas swaras).

Improvise within raga grammar using meend (glides), andolan (slow oscillation), gamak (heavy oscillation), murki/khaka (quick turns), kan swaras (grace notes), and well‑paced taans. Maintain raga chalan (typical movement) and avoid forbidden phrases.

Write a bandish (vocal) or gat (instrumental) that clearly states the raga’s pakad and outlines the tala’s sam (downbeat) and khali (empty beat). Use sargam (solfège), bols (tabla syllables), and poetic text (where applicable) aligned to the raga’s mood (rasa).

Balance melodic lead and rhythmic dialogue, giving space for sawaal‑javaab (call‑and‑response) with percussion.

Internalize raga through extensive riyaaz (practice), slow‑tempo vistaar, and taan patterns. Use Bhatkhande notation as a guide, but prioritize oral tradition and guru‑parampara. In performance, pace developments from alap to climactic drut, landing emphatically on sam to articulate form.