Vedic chant is the millennia‑old a cappella recitation of the Vedas in Vedic Sanskrit, preserved through an exacting oral tradition. It is characterized by three pitch accents (udātta, anudātta, and svarita), microscopic timing control, and codified pronunciation rules that ensure phonetic and semantic fidelity across generations.

Unlike melodic song, Vedic chant employs tightly delimited tonal contours rather than expansive scales, and it avoids harmony, accompaniment, and improvisation. Reciters render texts in metrical patterns such as Gāyatrī, Triṣṭubh, and Jagatī, using canonical recitation methods (pāṭhas) like Saṁhitā, Pada, Krama, Jatā, and Ghana to cross‑verify and stabilize the transmission.

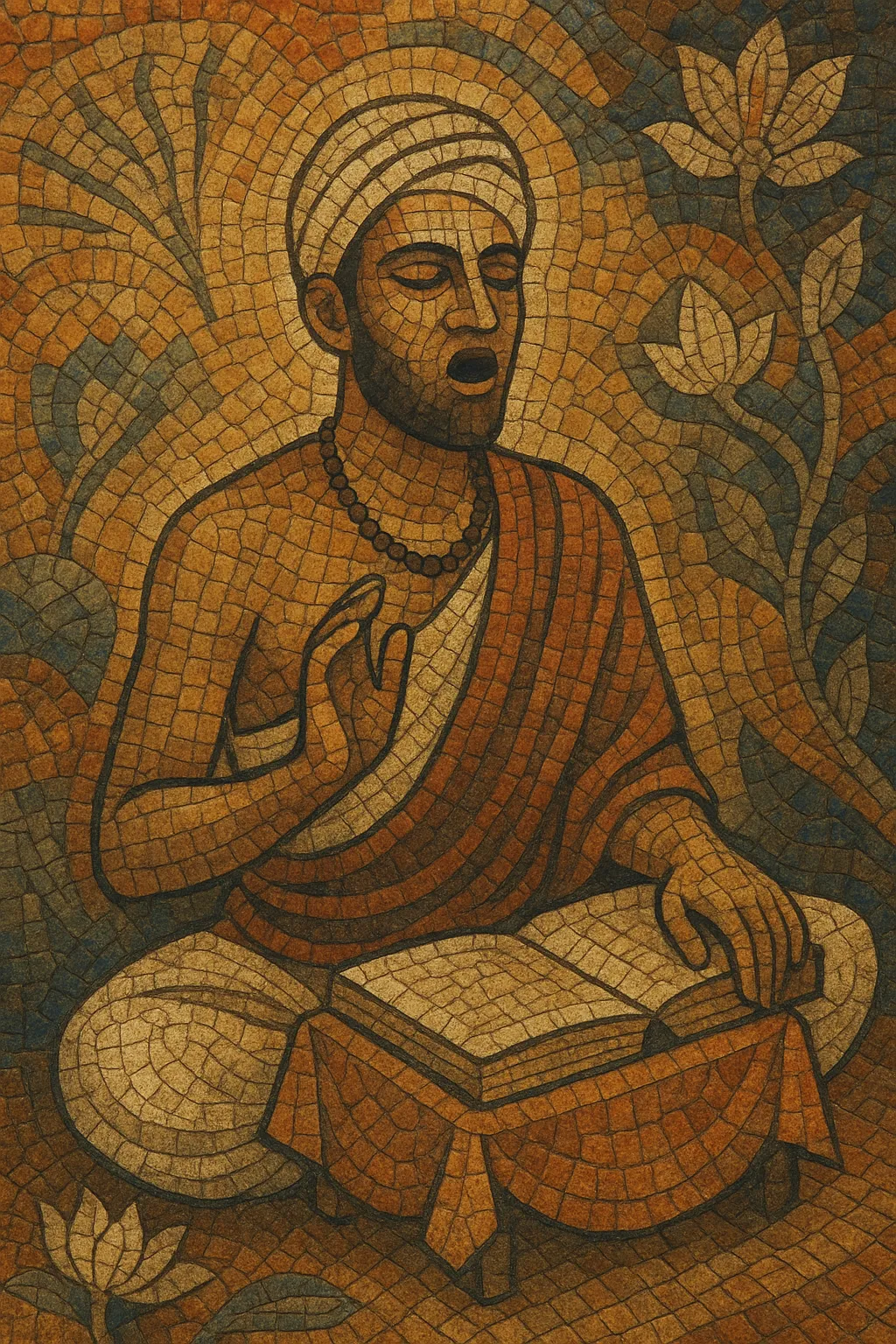

Performed by trained Brahmin lineages and Veda pāṭhaśālās, the chant functions as liturgy in Vedic rituals and as a vehicle for memorization, meditation, and sacred sound (śabda) practice. Its sonic austerity and ritual precision have profoundly shaped the aesthetics and pedagogy of South Asian classical and devotional music.

Vedic chant emerges from the early Indo‑Aryan ritual culture of the Indian subcontinent, with core layers of the Rigveda commonly dated to the second millennium BCE. From the outset, transmission was oral: specialized śākhās (branches/recensional schools) codified pronunciation (śikṣā), accents, and meter, while the Prātiśākhyas and ancillary texts laid down phonetic and sandhi rules. To safeguard verbatim preservation, teachers developed multiple, interlocking recitation formats (pāṭhas)—Saṁhitā (continuous), Pada (word‑by‑word), Krama (paired), and complex permutations like Jatā and Ghana—that serve as built‑in redundancy checks.

Distinct Vedas (Ṛg, Yajur—Śukla and Kṛṣṇa branches, Sāma—Kauthuma/Jaiminīya, and Atharva) maintain their own accentuation and melodic contours, with Sāmaveda being the most overtly melodic. Chanting accompanies śrauta and gṛhya rites, where sound correctness is itself efficacious. The three accent system—udātta (raised), anudātta (unraised), and svarita (falling)—structures pitch behavior, while metrical feet align recitation rhythm. Over centuries, regional lineages (e.g., Nambudiri in Kerala, schools in Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu, and Varanasi) maintained vibrant recitational styles.

From the nineteenth century onward, Indian pandits and international scholars documented the chant through philology, phonetics, and early audio recording. In 2003 UNESCO proclaimed Vedic chanting a Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity, later inscribed (2008) on the Representative List, highlighting both its antiquity and the rigorous training needed to sustain it. Contemporary pāṭhaśālās, peethams, and temple bodies continue the tradition, while select recordings and educational initiatives help transmission in changing social contexts.

Vedic chant’s disciplined pitch accent, metrical consciousness, and sacral view of sound informed foundational concepts of raga, tala consciousness in recitation, and devotional delivery. Through priestly and courtly continuities it shaped early classical forms (especially dhrupad) and devotional genres (bhajan, kirtan), and—by way of Indian classical music—later inspired global hybrids like raga rock.

Treat this as faithful recitation rather than composition. Select canonical Vedic Sanskrit passages (e.g., from Rigveda, Yajurveda, Samaveda) and learn the exact text, meter, and traditional accentuation. Use authoritative editions and lineages for guidance.

Employ the three accent system: udātta (raised), anudātta (unraised), and svarita (falling). Keep pitch motion minimal and rule‑bound—no harmony, chordal support, or melismatic ornamentation. In Sāmavedic contexts, apply the prescribed melodic contours for each chant.

Align delivery to Vedic meters such as Gāyatrī (3×8), Triṣṭubh (4×11), and Jagatī (4×12). Maintain an even, unhurried tempo that privileges clarity and breath control. Let metrical cadence govern phrasing rather than modern bar lines.

Render texts in Saṁhitā pāṭha (continuous) for liturgical flow, and employ Pada and Krama for pedagogical reinforcement. Advanced practitioners can perform Jatā and Ghana permutations to demonstrate and check exact transmission.

Use unison male or mixed male voices as per lineage custom; avoid instruments. Contemporary practice may include a discreet sruti reference (e.g., tanpura or shruti box) for pitch stability, but this is not traditional. Choose acoustically resonant spaces (temple halls, stone sanctums) that support natural reverberation.

Observe śikṣā rules: precise vowels, consonant clusters, nasality, visarga, and sandhi. Sustain vowels evenly, articulate consonants crisply, and allow micro‑pauses at sanctioned caesurae only. Accuracy supersedes expressive variability.

Respect ritual contexts and lineage permissions. When presenting outside liturgy, frame the recitation educationally, retaining textual integrity and avoiding fusion unless clearly labeled as adaptation.