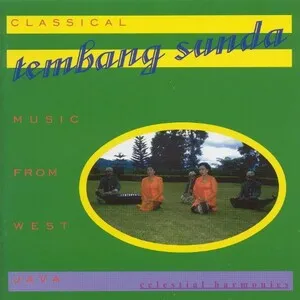

Tembang Sunda Cianjuran (often shortened to Cianjuran) is a refined Sundanese classical vocal tradition from West Java, Indonesia. It centers on an intimate sound world of voice accompanied by kacapi indung (large zither), kacapi rincik (small zither), and suling (end-blown bamboo flute).

The genre prioritizes nuanced vocal delivery, subtle ornamentation, flexible rhythm, and poetic text-setting in the Sundanese language. Its modal palette typically alternates between pelog-like and sorog/madenda (minor-like) atmospheres, producing a contemplative, nocturnal mood associated with aristocratic salons and cultured domestic performance.

Cianjuran’s repertoire is organized into categories such as papantunan (long narrative songs), rarancagan/jejemplang (recitative-ornamented styles), and panambih (shorter addendum pieces), each mapping classic Sundanese poetic forms (pupuh) like Kinanti, Sinom, Asmarandana, and Dangdanggula to established melodic formulas.

Cianjuran arose in the mid‑to‑late 1800s within aristocratic circles of Cianjur, West Java, where it was cultivated as a refined, indoor vocal art. Often linked to the patronage of the Cianjur regency elite (notably the regent R.A.A. Kusumahningrat, known as Dalem Pancaniti), the style crystallized practices of Sundanese poetic recitation into an art music with its own repertoire, modal idioms, and ensemble.

Unlike the larger, public sound of gamelan, Cianjuran developed an intimate chamber setting featuring two kacapi zithers and suling, supporting a lead vocalist (traditionally female, though not exclusively). Through the 19th and early 20th centuries, singers formalized categories such as papantunan (narrative songs), rarancagan/jejemplang (recitative-like forms with flexible rhythm), and panambih (shorter addendum pieces). The music adapted Sundanese pupuh meters, mapping poetic structure to melodic cadences and ornamental formulas (cengkok), while favoring rubato phrasing and elastic tempo.

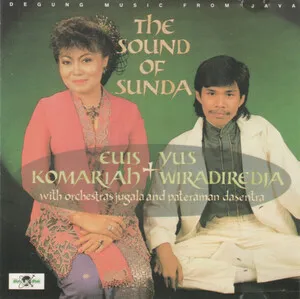

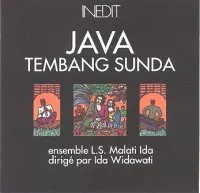

In the mid‑20th century, radio and commercial recordings helped move Cianjuran beyond aristocratic salons into urban cultural life, notably in Bandung and West Java at large. Conservatories and universities in West Java integrated Tembang Sunda into curricula, strengthening technique, repertoire standardization, and the training of new performers and accompanists. These institutions, alongside broadcasters and recording labels, preserved classic repertoire and fostered notable singers and kacapi/suling masters.

Into the late 20th and 21st centuries, Cianjuran retained its status as a signature Sundanese classical genre performed in concerts, community gatherings, cultural festivals, and on media platforms. Its melodic ornaments, modal sensibilities, and kacapi–suling textures informed related Sundanese styles—fueling the development of popular Sundanese song (Pop Sunda) and shaping vocal aesthetics absorbed by newer stage genres such as jaipongan—while continuing to represent a touchstone of Sundanese identity.