Minangkabau music is the traditional music of the Minangkabau people from West Sumatra, Indonesia. It spans vocal genres such as dendang (improvised, proverbial song), religious performance forms like indang, and theatrical music for the martial-arts dance drama randai.

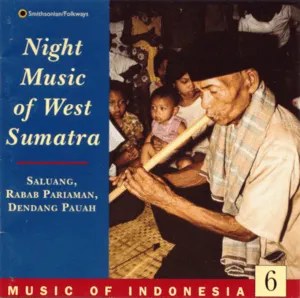

Instrumental idioms center on talempong (small kettle-gongs) played in interlocking patterns, saluang (an end-blown bamboo flute using circular breathing), rabab/rabab pasisia (a spike fiddle), gandang (drums), tasa, serunai (shawm), and a range of idiophones and aerophones such as pupuik batang padi (rice-stalk trumpet). The music alternates between fluid, free-rhythm singing and tightly cyclical, groove-based ensemble textures.

Melodically, pieces draw on regional modal sensibilities and limited-scale frameworks (often pentatonic or heptatonic) tailored to the tuning of talempong sets. Rhythmically, talempong pacik ensembles create interlocking ostinati in compound meters (commonly felt as 6/8 or 12/8), while procession styles (tambua tasa) emphasize driving duple pulses. Performances occur at weddings (baralek), communal festivities, theatre, and devotional gatherings.

Minangkabau music emerges from the matrilineal Minangkabau culture of West Sumatra, with roots in ritual, community celebrations, and oral poetry. Core practices—such as dendang accompanied by saluang, interlocking talempong ensembles for dance, and the Sufi-influenced group song-and-drumming of indang—were well established by the 19th century, though many elements are much older.

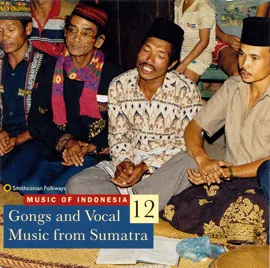

Two broad currents coexisted: vocal-poetic traditions (dendang, rabab pasisia balladry) that privilege narrative, proverb, and improvisation, and ensemble dance/theatre music (talempong pacik for social dance, randai for sung theatre that integrates silek—the local martial art). The idiom connects to wider gong-chime cultures of the archipelago while retaining distinct Minangkabau tunings, repertoires, and performance roles.

Centuries of Islamic scholarship in Minangkabau lands fostered devotional music (zikir/indang) and poetic forms (pantun, syair), blending Malay literary aesthetics with local styles. Trade and migration along Sumatra’s coast (pesisir) encouraged exchanges with Malay, Acehnese, and broader Indian Ocean musical practices, shaping instruments (serunai, rabab) and vocal aesthetics.

In the mid-20th century, recording and radio helped codify repertoires and popularize star singers. Urban ensembles occasionally adopted diatonic talempong sets and incorporated guitars or accordions. Troupes toured nationally, and Minangkabau artists based in Jakarta popularized Minang-themed songs.

Since the late 20th century, traditional idioms have inspired new offshoots: pop Minang brings modern production to Minang melodies and language, while talempong goyang adapts gong-chime textures to dance-pop frameworks. At the same time, community-based performance (baralek, randai, religious events) sustains the core traditions, and younger musicians document and revitalize local styles through education and digital media.