Malay music refers to the traditional and popular musical practices of the ethnic Malay communities of the Malay Peninsula and surrounding regions, with Malaysia as its primary cultural center.

It blends indigenous Malay aesthetics with strong influences from Arab-Islamic, Indian (especially Hindustani/ghazal), Chinese, and Portuguese traditions. Core song-forms include asli (lyrical and ornamented), inang (courtly), joget (lively dance in 6/8), zapin (Hadhrami Arab-derived dance music), ghazal Johor (Malay interpretation of the Indo-Persian ghazal), and dondang sayang (improvised pantun poetry over graceful melodies).

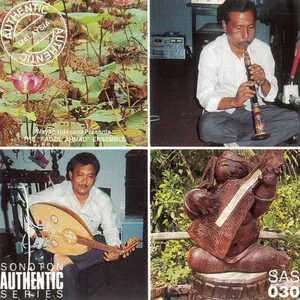

Typical instruments include gambus (Malay oud), biola (violin), harmonium, accordion, serunai (reed shawm), rebab (spike fiddle), kompang and rebana (frame drums), marwas (small hand drums), gendang (barrel drums), and occasionally tabla. Melodies favor pentatonic and heptatonic frameworks enriched with maqam-like inflections, while lyrics draw on pantun (quatrain) poetry, courtly love, moral teachings, and reflections on nature and adat (custom).

Malay music coalesced over centuries as the musical expression of Malay courts and coastal communities. Indigenous song-forms such as asli and inang were shaped by courtly etiquette and poetic pantun, while maritime trade brought Hadhrami Arab, Indian, and Chinese influences to entrepôts on the Malay Peninsula. Frame drums (kompang, rebana) and the gambus entered through Islamic devotional and Arab musical traditions, while violin, accordion, and harmonium arrived via colonial and cosmopolitan circuits.

By the 1800s, the Malay repertoire expanded through sustained contact with Arab, Indian, and Portuguese cultures. Zapin (from Hadhrami Arabs) took root as a devotional dance music before becoming secularized performance, characterized by marwas drums and syncopated steps. Joget, with links to Iberian/Portuguese dance repertoires, became a popular social dance in 6/8. Ghazal Johor emerged as Malay musicians adapted Indo-Persian poetic song with harmonium, violin, tabla, gambus, and Malay rhythmic sensibilities.

The early 20th century saw orkes Melayu (Malay orchestras) popularize a modernized ensemble sound combining Malay melodies, Arab/Indian modality, and Western instruments. With recording studios, cinema, and radio (notably RTM), artists such as P. Ramlee helped canonize a new pan-Malay songbook that moved fluidly between asli, joget, and popular ballads, preserving traditional aesthetics while adopting modern harmony and arrangement.

After independence, Malay music persisted on stage and airwaves while intersecting with pop, rock, and film music. Dondang sayang and mak yong theatre continued as heritage forms; zapin ensembles proliferated in schools and cultural institutions. Cross-Straits musical exchange with Indonesia linked Malay music to keroncong and later to dangdut’s development, while domestic pop incorporated Malay melodic turns and poetic imagery.

Malay music remains vital through cultural festivals, university ensembles, and state arts bodies. Contemporary singers blend asli ornamentation with pop and R&B, while dedicated groups keep ghazal Johor and zapin alive with careful pedagogy. New recordings highlight the gambus-led chamber aesthetic, and collaborations with world, jazz, and cinematic music continue to present Malay song-forms to global audiences.

%2C%20Cover%20art.webp)