Southern African music is an umbrella for the popular and traditional sounds of countries at the subcontinent’s tip, especially South Africa, Zimbabwe, Zambia, Mozambique, Namibia, Botswana, Lesotho, and Eswatini.

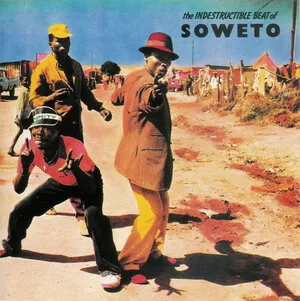

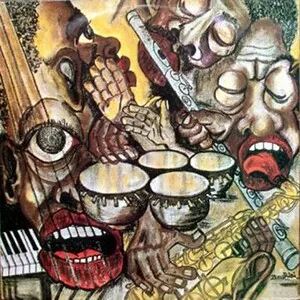

It blends indigenous polyrhythms, call-and-response vocals, and cyclical melodic vamps with elements absorbed from church hymnody, brass bands, jazz, blues, soul, reggae, and later electronic dance music. Common textures range from powerful choral styles (isicathamiya/mbube) and guitar-driven folk-pop (maskandi, jit, sungura) to horn-led township jazz and dancefloor forms (kwela, marabi, kwaito, gqom, amapiano).

Lyrically, it addresses everyday life, love, moral teaching, satire, urban modernity, and political resistance. The region’s multilingual reality (e.g., Zulu, Xhosa, Shona, Ndebele, Sotho, Tswana, English, Afrikaans, Portuguese) is central to its identity and expressive breadth.

Indigenous musical systems across Southern Africa long predate recording. Communal singing with antiphony, polyrhythmic percussion, bow and lamellophone (mbira/kalimba) traditions, praise poetry, and dance ceremonies formed the deep vocabulary that would animate 20th‑century styles.

Mission schools and churches spread hymnody and part-singing, merging with local vocal practices and catalyzing choral idioms like isicathamiya/mbube. Colonial and military presence introduced brass bands, while imported recordings of ragtime, jazz, and blues inspired urban marabi and the pennywhistle-driven kwela. Townships became creative hubs where indigenous cycles met Western harmony and instrumentation.

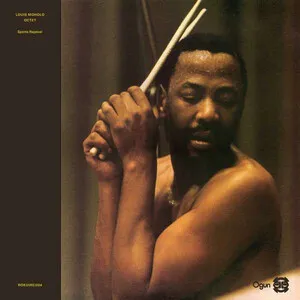

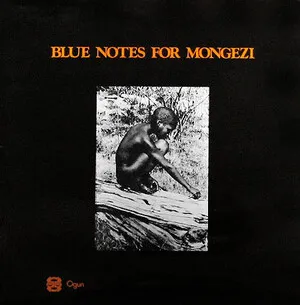

Township jive and mbaqanga flourished with propulsive basslines, guitars, and vocal trios (e.g., Mahotella Queens). Zimbabwe’s chimurenga (Thomas Mapfumo) translated mbira patterns to electric guitar, later feeding into jit and sungura. Jazz modernists (Hugh Masekela, Abdullah Ibrahim) exported a uniquely Southern African swing. Music served as resistance under apartheid and other struggles, with artists like Miriam Makeba becoming global symbols.

House culture met township sensibilities to forge kwaito’s slowed, bass-rich grooves, then mutated into hyperlocal club forms such as gqom and amapiano. Cape jazz continued, and cross-pollination with reggae/dancehall shaped scenes like zimdancehall. Digital production and global diaspora networks amplified regional sounds, positioning Southern African music as a driver of contemporary African pop.

Southern African artists and idioms have influenced world jazz, choral music, indie and alternative fusions, and global dance music, while remaining grounded in communal performance, dance, and storytelling.