Motswako is a Southern African hip hop style whose name means "mixture" in Setswana, reflecting its hallmark code‑switching between Setswana and English and its blend of boom‑bap hip hop with local street rhythms.

Typical motswako tracks ride mid‑tempo grooves (roughly 85–105 BPM), pairing punchy, sample‑driven drums with warm basslines and chantable hooks. Artists prioritize nimble flows, storytelling, and wordplay that reference Tswana idioms, proverbs, and everyday township life.

The sound emerged from the North West province (Mahikeng) and neighboring Botswana, then spread into South Africa’s mainstream in the 2000s, helping define a distinctly regional voice within African hip hop.

Motswako took shape in and around Mahikeng (North West province, South Africa) and across the border in Botswana. Local MCs began merging the cadence and beats of old‑school and boom‑bap hip hop with township party sensibilities and Setswana/English code‑switching. Early adopters framed the style as a cultural statement: rap that sounded like home and spoke directly to Tswana youth.

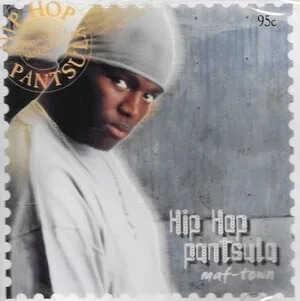

Pioneers such as HHP (Hip Hop Pantsula), Tuks Senganga, and the group Morafe helped set the template—story‑rich verses in Setswana, chorus hooks designed for crowd chant, and production that balanced soulful samples with kwaito‑seasoned bounce. Radio play, street mixtapes, and local shows cemented motswako as a movement, not merely a dialect variant of hip hop.

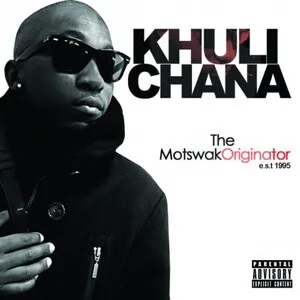

Khuli Chana’s high‑profile releases and Cassper Nyovest’s pop‑crossover success carried motswako aesthetics into South Africa’s mainstream. At the same time, Botswana voices like Zeus kept the cross‑border identity vibrant. The scene broadened with new talents (e.g., Fifi Cooper, Mo’Molemi) and collaborative crews and producers who refined the sound’s polish while preserving its language mix and regional storytelling.

Motswako remains a reference point for Southern African rap identity. Even when artists shift into trap or pop‑rap palettes, the signatures—code‑switching, Tswana cultural references, and chant‑friendly hooks—continue to influence writing styles, performance energy, and how Southern African hip hop presents itself globally.