Blues is an African American musical tradition defined by expressive "blue notes," call-and-response phrasing, and a characteristic use of dominant-seventh harmony in cyclical song forms (most famously the 12‑bar blues). It is as much a feeling as a form, conveying sorrow, resilience, humor, and hard-won joy.

Musically, blues commonly employs the I–IV–V progression, swung or shuffled rhythms, and the AAB lyric stanza. Melodies lean on the minor/major third ambiguity and the flattened fifth and seventh degrees. Core instruments include voice, guitar (acoustic or electric), harmonica, piano, bass, and drums, with slide guitar, bends, and vocal melismas as signature techniques.

Over time the blues has diversified into regional and stylistic currents—Delta and Piedmont country blues, urban Chicago and Texas blues, West Coast jump and boogie-woogie—while profoundly shaping jazz, rhythm & blues, rock and roll, soul, funk, and much of modern popular music.

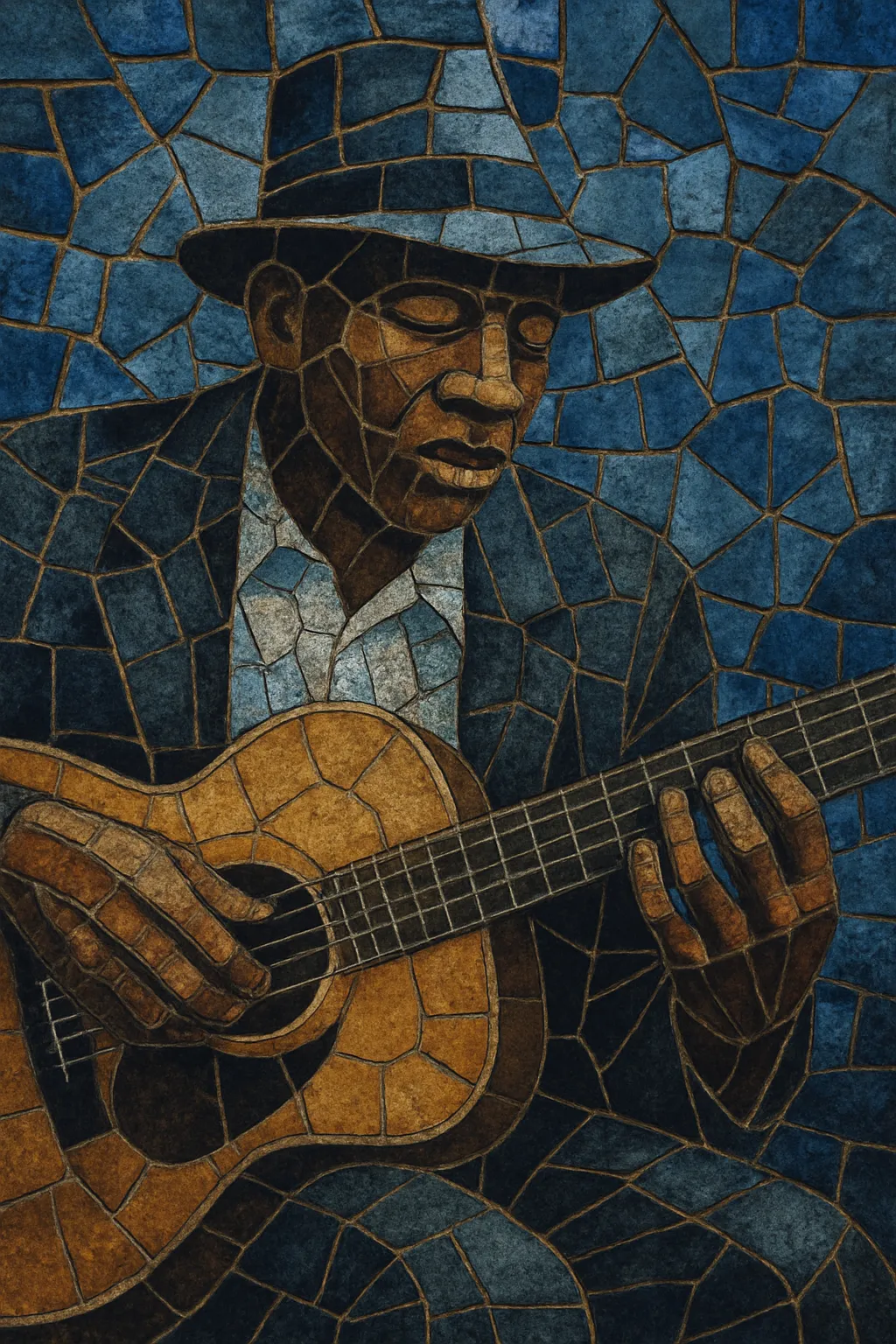

Blues emerged in the post‑Emancipation American South, especially in the Mississippi Delta and surrounding regions. It drew on African American work songs, field hollers, ring shouts, spirituals, and church music, blending West African musical aesthetics (call‑and‑response, flexible intonation, polyrhythm) with European harmonies and ballad forms. Early practitioners were itinerant singers and guitarists performing at juke joints, levee camps, turpentine camps, and house parties.

The 1920s “race records” era documented blues for the first time. Classic female blues singers like Mamie Smith, Ma Rainey, and Bessie Smith recorded with small jazz ensembles, bringing the music to national audiences. In parallel, country (rural) blues artists such as Charley Patton and Blind Lemon Jefferson popularized guitar‑based solo styles and established the vocabulary of the Delta and Texas traditions.

The Great Migration carried the blues to northern cities. In Chicago, amplified guitar, electric bass, harmonica, piano, and drums forged a powerful urban sound. Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, and Willie Dixon defined the electric Chicago blues, while T‑Bone Walker’s electric soloing catalyzed modern lead guitar. Boogie‑woogie piano and jump blues overlapped with swing and early rhythm & blues, setting the stage for rock and roll.

Blues phrasing, harmony, and feel were foundational for R&B, rock and roll, and later rock. British and American blues revivals (e.g., the UK blues boom) reintroduced artists like Robert Johnson and Muddy Waters to new audiences and inspired bands that transformed popular music. Blues‑rock, soul, and funk incorporated blues tonality and grooves while expanding instrumentation and production.

Modern blues spans traditional acoustic styles, high‑gain electric sounds, and genre fusions with jazz, rock, gospel, hip hop, and world music. Festivals, archival reissues, and education have preserved regional variants (Delta, Piedmont, Texas, West Coast) while new artists advance technique, songwriting, and social storytelling within the idiom.

Start with the 12-bar blues in a key like A, E, or G. Use dominant 7th chords for I, IV, and V (e.g., A7–D7–E7).

•Common layouts:

• Basic: I7 | I7 | I7 | I7 | IV7 | IV7 | I7 | I7 | V7 | IV7 | I7 | V7

• Quick change: I7 | IV7 | I7 | I7 | IV7 | IV7 | I7 | I7 | V7 | IV7 | I7 | V7

• Minor blues: i7 | i7 | i7 | i7 | iv7 | iv7 | i7 | i7 | V7 | iv7 | i7 | V7

•Use turnarounds (e.g., I7–VI7–II7–V7) at bar 11–12 to cycle back. 8‑bar and 16‑bar variants are also common.

Chords by bar: A7 | D7 | A7 | A7 | D7 | D7 | A7 | A7 | E7 | D7 | A7 | E7

Scale palette: A minor pentatonic (A–C–D–E–G) + blue note (Eb) and occasional C# for major/minor 3rd color.

Groove: 12/8 shuffle with a swung eighth‑note triplet feel.