Southern African folk music is an umbrella for indigenous song, dance, and instrumental traditions found across countries such as South Africa, Zimbabwe, Mozambique, Botswana, Lesotho, Eswatini, and Namibia. It centers the human voice, community participation, and cyclical rhythms, with performance contexts ranging from daily work and praise poetry to rites of passage and communal celebrations.

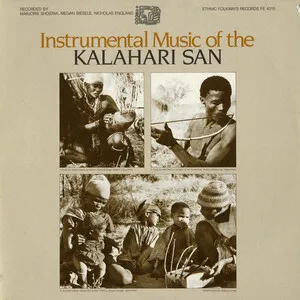

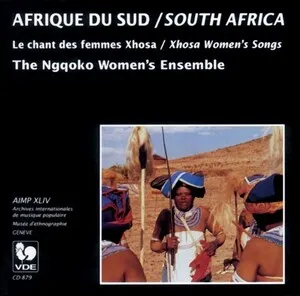

Common features include call-and-response singing, handclaps and foot-stomps that articulate polyrhythms (often 3:2 and 12/8 feels), and harmonic textures built from parallel thirds, fourths, and rich choral bass lines. Instruments vary by people and locale: mbira/nyunga-nyunga (lamellophones), marimbas, musical bows (uhadi, umakhweyana), rattles (hosho), drums (ngoma), horns, and later pennywhistles and guitars. Lyrics blend storytelling, praise, social commentary, and spirituality, delivered in languages such as isiZulu, isiXhosa, Sesotho, Setswana, Shona, Tsonga, Ndebele, and others.

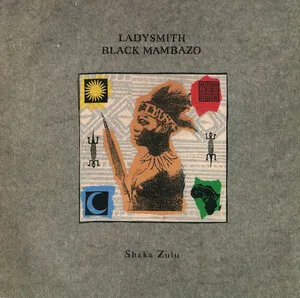

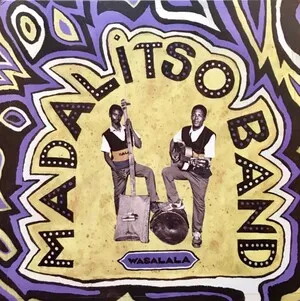

While deeply rooted in precolonial practices, the genre evolved through contact with mission hymnody and urbanization, giving rise to modern offshoots like isicathamiya, mbube, maskanda, mbaqanga, kwela, chimurenga, marrabenta, sungura, and Tsonga-derived dance forms. Its pulse and communal ethos continue to shape Southern Africa’s musical identity.

Southern African folk music predates written history, emerging from community ceremony, labor, and storytelling. Vocal polyphony, praise poetry, call-and-response, and polyrhythmic handclapping formed its core, while instruments like mbira (Shona), uhadi and umakhweyana bows (Xhosa/Zulu), ngoma drums, and marimba ensembles developed in distinct cultural zones.

The 1800s brought missionary schools and church choirs, introducing hymnody and four-part harmony. Local musicians adapted these ideas to indigenous aesthetics, reinforcing choral traditions that later informed isicathamiya and mbube. Urban migration fostered new ensembles and repertoires, while guitars and concertinas entered folk practice (e.g., Zulu maskanda), and pennywhistles helped seed kwela.

With increased recording and radio, indigenous rhythms and melodies fused with modern instrumentation. South Africa saw mbube/isicathamiya, mbaqanga, maskanda, and township styles flourish. In Zimbabwe, guitar-driven folk modernisms like chimurenga and later sungura adapted mbira cycles into band formats. Mozambique’s marrabenta blended local melodies with dance-band idioms. These innovations kept folk DNA at the center while embracing new sonic palettes.

Artists such as Miriam Makeba, Ladysmith Black Mambazo, Thomas Mapfumo, and Oliver Mtukudzi carried Southern African folk idioms worldwide. Contemporary electronic and dance forms (e.g., shangaan electro, Tsonga disco) continue to reinterpret folk rhythms and call-and-response patterns. Despite modernization, community participation, cyclical groove, and storytelling remain the living heart of Southern African folk music.