Your digging level

Description

Nueva cumbia chilena is a 2000s revival and reinvention of cumbia in Chile that blends the classic Colombian-rooted rhythm with Chilean popular music traditions and contemporary urban sounds.

It typically features brass-heavy arrangements, percussion-led grooves, and catchy call-and-response vocals, mixing influences from ska, rock, reggae, salsa, and local folk forms such as cueca.

The scene arose in Santiago and Valparaíso, where bands reimagined cumbia for festivals, neighborhood parties, and large dance floors, emphasizing communal dancing, humor, social commentary, and a celebratory spirit.

Though rooted in retro aesthetics, the style often incorporates modern production, big-band energy, and cosmopolitan touches (Balkan brass, ska-punk, and Latin alternative), making it a bridge between tradition and 21st‑century Latin urban culture.

History

Cumbia has been popular in Chile since the mid‑20th century, but the “nueva cumbia chilena” movement crystallized in the 2000s. Bands connected to the coastal and capital city live circuits—especially around Valparaíso and Santiago—revived cumbia with a post‑dictatorship, festival‑oriented sensibility. Early catalysts included musicians linked to rock, ska, and brass ensembles who embraced the danceability of cumbia while infusing it with local folk colors (cueca), reggae skank, salsa spice, and a punk‑DIY performance ethos.

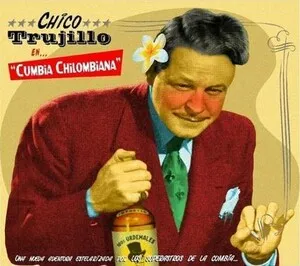

Groups like Chico Trujillo and Banda Conmoción gave the sound a large, jubilant brass core, while Juana Fé, Santaferia, and Villa Cariño folded in urban grooves and socially conscious lyrics. The result was a vibrant, street‑level party music that honored classic cumbia patterns but favored rowdy choruses, collective singing, and playful theatricality—qualities that translated to packed clubs, university parties, and summer festivals.

In the 2010s, the movement broadened with new ensembles (e.g., La Combo Tortuga) and a growing national audience. The scene’s success encouraged cross‑genre collaborations and helped normalize cumbia within Chile’s indie and alternative circuits. Bands toured across Latin America, sharing bills with electrocumbia and digital cumbia acts, and helped spur a broader regional cumbia revival.

Nueva cumbia chilena reaffirmed cumbia as a living cultural commons in Chile. It nurtured a dance‑floor‑first, community‑minded approach to live performance and influenced subsequent fusions—from indie‑cumbia hybrids to electronics‑enhanced variants—while preserving the joyous, participatory essence of cumbia.

How to make a track in this genre

Start with the classic cumbia pulse: a steady 4/4 with the characteristic off‑beat/clave feel. Use congas, güiro, timbales, and drum set to interlock syncopations. Keep tempos in a comfortable dancing range (roughly 90–110 BPM), allowing for swagger and swing.

Build a brass‑forward frontline (trumpets, trombones, saxes) for riffs, countermelodies, and call‑and‑response hooks. Add electric bass (often playing tumbao‑like patterns), electric/acoustic guitars for rhythm and occasional ska upstrokes, and keyboards or accordion for chordal glue and melodic fills. Arrange in sections that alternate between tight riffs and open, chant‑friendly choruses.

Favor bright, diatonic progressions (I–IV–V, ii–V–I) with occasional modal color and salsa‑style turnarounds. Melodies should be singable and repetitive, designed for crowd participation. Brass lines can quote traditional cumbia figures while introducing Chilean folk motifs.

Write inclusive, communal lyrics that mix humor, everyday stories, romance, and social observation. Use catchy refrains, call‑and‑response shouts, and group choruses. Balance celebratory tone with occasional commentary, reflecting the genre’s roots in popular neighborhoods and festival culture.

Keep productions lively and organic: prioritize room mics for brass and percussion, and emphasize bass and güiro in the mix. Live, encourage audience clapping, dancing, and sing‑alongs. Visuals (banners, bright colors) and processional entrances echo the street‑party lineage of the style.