Your digging level

Description

Marabi is a South African urban dance music that emerged in the townships around Johannesburg during the 1920s. It is built on hypnotic, cyclical chord vamps—often a simple I–IV–I–V loop—played on cheap pedal organs or upright pianos in informal drinking houses known as shebeens.

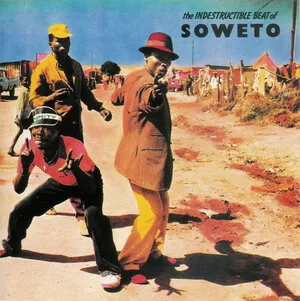

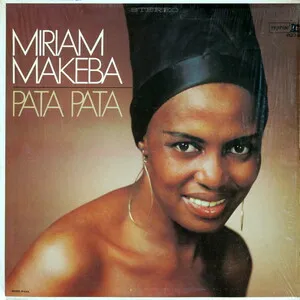

Blending African melodic phrasing and call-and-response with the syncopation and harmonic language of American ragtime, stride, and early jazz/swing, marabi created an irresistibly danceable groove. As the style moved from small shebeen settings to larger ensembles, saxophones, trumpets, guitar/banjo, bass, and drums amplified its energy and helped define what became known as “township jazz.” Marabi’s infectious vamps and social vitality laid the groundwork for later South African genres such as kwela and mbaqanga.

History

Marabi arose in the rapidly growing mining-town townships of early 20th‑century South Africa, especially around Johannesburg. In shebeens—informal bars where working-class Black communities gathered—musicians used affordable pedal organs and upright pianos to craft cyclical, trance-like vamps. These loops supported hours of dancing and socializing. The idiom blended African vocal sensibilities and neighborhood song traditions with imported American influences (ragtime, stride, early jazz/swing) heard via records, films, and touring bands, as well as mission church harmonies.

By the 1930s, marabi motifs migrated from keyboard solos to combos and big bands, adding saxophones, trumpets, guitar/banjo, bass, and drums. Groups such as the Jazz Maniacs and the Merry Blackbirds popularized a township swing sound rooted in marabi harmony and rhythm. Sophiatown—Johannesburg’s famed multiracial cultural hub—became a crucible for this music, nurturing performers, dance halls, and recording activity.

Urban removals and censorship under apartheid disrupted cultural life, yet marabi’s DNA persisted. Its vamp-driven harmony and township groove fed directly into kwela (pennywhistle jive) and, later, into mbaqanga’s hard-driving, guitar-led dance music. Jazz artists like Abdullah Ibrahim (Dollar Brand) reinterpreted marabi vamps in concert works and iconic recordings, ensuring the idiom’s survival beyond the shebeen.

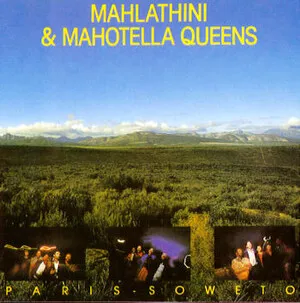

From the 1980s, revivalist bands such as the African Jazz Pioneers rekindled the big-band township sound for new audiences, while marabi’s cyclical harmony, swing feel, and call‑and‑response aesthetics remain a foundation for South African jazz, popular dance styles, and stage productions. Today, marabi is recognized as a cornerstone of South Africa’s musical identity and a key link between early township dance culture and later popular genres.