Your digging level

Description

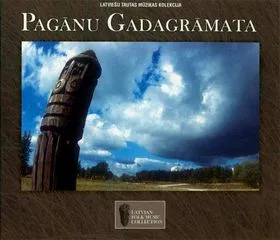

Latvian folk music is the traditional music of the Latvian people, centered on the daina—short, tightly structured lyric songs in trochaic meter that often use four-line quatrains and nature- or myth-themed imagery. Melodies are typically narrow in range, modal (frequently Aeolian and Dorian), and performed either solo or in unison/heterophony with a characteristic sustained drone (burdons).

Core timbres come from the kokle (a plucked box zither), bagpipes (dūdas), various flutes (stabules), fiddles (gīga), and later accordion; voice remains the primary instrument. Repertoires include work songs, wedding and ritual songs, lullabies, and seasonal songs—especially Jāņi (Midsummer) pieces with refrains like “Līgo.” Dance music incorporates European couple dances—polka, mazurka, schottische, and waltz—adapted to local style.

Beyond the village, Latvian folk music also exists as a mass choral phenomenon through the Song and Dance Celebration tradition, where large choirs perform folk-based arrangements that embody communal memory and national identity.

History

Latvian folk music grows out of a deep oral tradition whose core is the daina—compact poetic songs encompassing daily life, the natural world, and pre-Christian cosmology (Dievs, Māra, Laima, Pērkons). While the songs themselves long predate written sources, systematic notations and textual collections began appearing between the 16th and 18th centuries through local clergy and scholars.

In the 1800s, during the Latvian National Awakening, collecting and codifying dainas became a cultural mission. Krišjānis Barons’s monumental “Dainu skapis” (Cabinet of Folksongs) in the late 19th century preserved hundreds of thousands of texts. The first Latvian Song Festival (1873, Rīga) inaugurated a mass-choral tradition that fused folk materials with arranged choral practices, solidifying folk song as a pillar of national identity. European social dances—polka, mazurka, schottische, and waltz—were adopted and localized in village dance bands.

Across the 20th century, war, occupation, and political shifts reshaped performance contexts. Under Soviet rule, state folk ensembles and folklore collectives maintained and stylized traditions; the mass Song and Dance Celebration continued as a carefully curated but culturally significant event. Meanwhile, local singers and instrumentalists kept regional styles (e.g., Suiti drone singing) alive in communities.

In the 1980s, the Baltic “Singing Revolution” highlighted folk song and choral participation as vehicles for non-violent resistance and identity, contributing to Latvia’s independence (1991). Post-independence, fieldwork, community ensembles, and new performers revitalized kokle playing, drone polyphony, and regional repertoires, while contemporary groups began to fuse folk idioms with modern genres.

The Latvian Song and Dance Celebration is inscribed by UNESCO as part of the Baltic song celebration tradition, and the Suiti cultural space (including its distinctive drone singing) is also recognized by UNESCO. Today, Latvian folk music thrives both in community practice and on professional stages, influencing folk-rock, pagan folk, and folk metal, and representing Latvia on international festival circuits.

How to make a track in this genre

For ritual/work songs, use flexible, speech-like rhythm. For dances, adopt steady meters from village repertoire:

•Polka and schottische: 2/4 or 4/4 with strong offbeat accompaniment.

•Mazurka: lilting 3/4 with characteristic accent on beat 2 or 3.

•Waltz: flowing 3/4 at moderate tempo.