Armenian folk music is the traditional music of the Armenian people, shaped by centuries of oral transmission, regional dance practices, bardic (ashugh) song, and village ritual. It is marked by expressive, melismatic vocals, modal melodies, and distinctive timbres—most famously the plaintive sound of the duduk (an apricot-wood double reed) accompanied by a drone.

Core instruments include the duduk (with a second "dam" duduk providing the continuous drone), zurna (shawm), dhol/daul (double-headed drum), shvi and blul (end-blown flutes), kamancha (spike fiddle), kanun (zither), tar (long-necked lute), and, in modern contexts, violin and accordion. Dance repertory (such as kochari, shalakho, yarkhushta) often uses asymmetrical meters like 5/8, 7/8, 9/8, and 10/8, articulated as additive groupings (for example, 2+2+1 or 3+2+2+3). Melodic language is modal and ornamented, drawing on maqāmic pitch collections with microtonal inflections.

Textually, songs range from love lyrics and pastoral imagery to historical epics and laments, reflecting both village life and national memory. The repertoire was extensively collected and systematized by Komitas (Soghomon Soghomonian) in the late 19th–early 20th century, and its instruments—especially the duduk—have become global emblems of Armenian sound.

Armenian folk music descends from ancient bardic and village practices that predate Christianity, with early professional minstrels (gusans) performing narrative and lyrical songs for courts and communities. Over centuries, regional dances and ritual songs formed a varied local repertoire tied to the Armenian highlands and the South Caucasus.

Between the 17th and 18th centuries, the ashugh tradition (urban bards who sang and accompanied themselves on long‑necked lutes) flourished. Figures like Sayat‑Nova (1712–1795) exemplified refined poetic song that blended Armenian language and modal practice with broader Caucasian and Near Eastern aesthetics.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Komitas Vardapet (1869–1935) collected thousands of village songs, transcribing and arranging them while emphasizing their modal logic and unique intonation. His work preserved repertory threatened by displacement and modernity, and helped distinguish Armenian melodic and rhythmic features from neighboring traditions.

During the Soviet period, state ensembles (notably the Armenian State Song and Dance Ensemble founded by Tatul Altunyan) staged stylized versions of village dances and songs. Folkloric orchestration with accordion, clarinet, and sectional choruses brought Armenian folk to concert halls and radio, while local master musicians sustained rural performance practice.

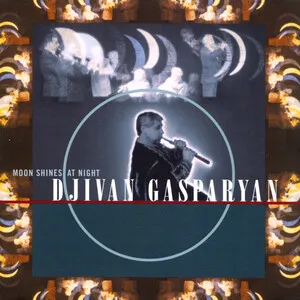

Following the Armenian Genocide and later migrations, diaspora communities in the Middle East, Europe, and the Americas maintained regional song dialects (e.g., Dikranagerd, Van, Musa Dagh). From the late 20th century, artists and ensembles in Armenia and abroad sparked revivals focused on historically informed performance (duduk trios, small village ensembles). The duduk’s timbre captured global attention—recognized by UNESCO as part of the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity—appearing in film, television, and world-music collaborations.

%2C%20Cover%20art.webp)